If you’re like us, you probably gave Hula-Hooping a whirl as a kid. And if you’re like us, you probably also abandoned the activity as you grew up — because, at the risk of being overly punny, it can feel as though you have to jump through hoops just to sustain the spin for more than a few seconds.

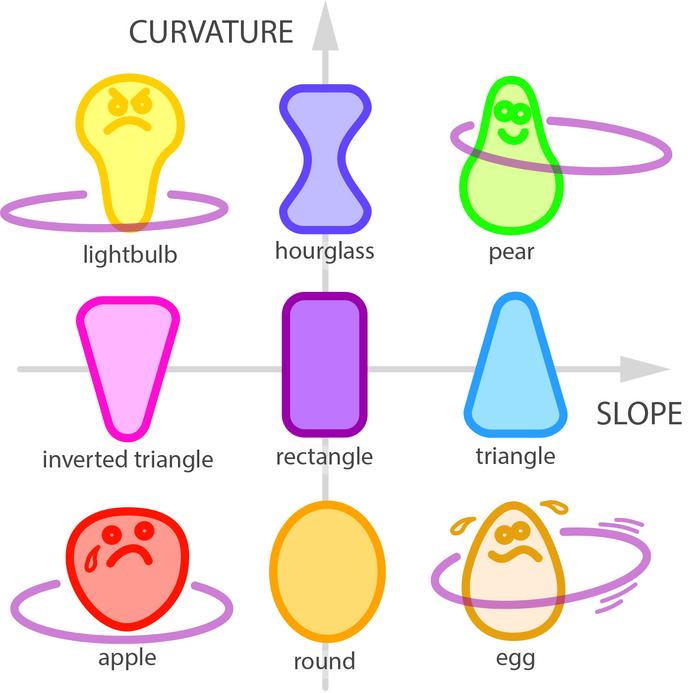

It turns out there’s a science-backed reason why this seemingly simple motion is so dang difficult for some people. Apparently, keeping the plastic tube in the air has more to do with your body shape than your movements, and people with “pear” and “hourglass” figures have a clear advantage.

This finding is based on a recent study from New York University that sought to understand the physics and mathematics behind Hula-Hooping, which has seen a resurgence in popularity in recent years as a form of exercise.

“We were specifically interested in what kinds of body motions and shapes could successfully hold the hoop up and what physical requirements and restrictions are involved,” senior author Leif Ristroph said in a statement, adding: “We were surprised that an activity as popular, fun, and healthy as Hula-Hooping wasn’t understood even at a basic physics level.”

NYU’s Applied Mathematics Lab

To get to the bottom of it, the researchers 3D-printed miniature robots in different shapes to mimic various human body types, including ones they dubbed “apples,” “eggs,” and “lightbulbs.” Then, to imitate the real game, they launched plastic hoops six inches in diameter on the robots. The machines were activated to “realize gyration” via motors while high-speed video recorded their movements.

The result? Keeping the hoops from falling for a significant period of time required two attributes: “Hips,” or a sloping surface, to push the hoop up, and a “curvy waist” for stability. On the flip side, “all trials with a cylindrical body fail[ed] to suspend the hoop,” the study noted.

NYU’s Applied Mathematics Lab

“People come in many different body types — some who have these slope and curvature traits in their hips and waist and some who don’t,” Ristroph said in the statement. “Our results might explain why some people are natural hoopers and others seem to have to work extra hard.”

The researchers also found that simply getting the hoop going was possible for all the robots studied — it was the keeping it going part that was more difficult. “In all cases, good twirling motions of the hoop around the body could be set up without any special effort,” said Ristroph. This might explain why some of us get our hopes up when we start Hula-Hooping, only to have them come crashing down (along with the hoop) seconds later.

As validating as these results may be, their implications go beyond explaining playground memories. “As we made progress on the research, we realized that the math and physics involved are very subtle, and the knowledge gained could be useful in inspiring engineering innovations, harvesting energy from vibrations, and improving in robotic positioners and movers used in industrial processing and manufacturing,” Ristroph noted.

But if you’re one of the many who have hopped on the Hula-Hooping exercise train and don’t have a “pear” or “hourglass” figure, don’t let these results discourage you. The activity is a great way to burn calories, get your heart rate up, and strengthen your core — and while scientists identified ideal body types, practice and the right technique can help anyone do it. Follow these tips to get your hoop in the air (for more than a few seconds), and try this beginner workout to get your feet wet (and your hips moving).

RELATED: With “Exercise Snacking,” You Can Boost Your Fitness Without Hitting the Gym