Eggs have been a healthy breakfast staple for thousands of years. Even the Aztec emperor Montezuma is said to have eaten them with his morning summer meals, according to the BBC — though his weren’t from a chicken, but an insect, the Axayácatl fly. Ahuautle, also known as “Mexican caviar,” was considered a food of the gods, lauded for its strength-giving properties. Although it’s no longer used in ceremonies for the Aztec fire god Xiuhtecuhtli, it remains an integral part of Mexican culture. But waning interest and increasing costs have some fearing it might become a thing of the past. A handful of dedicated locals are trying to prevent that from happening.

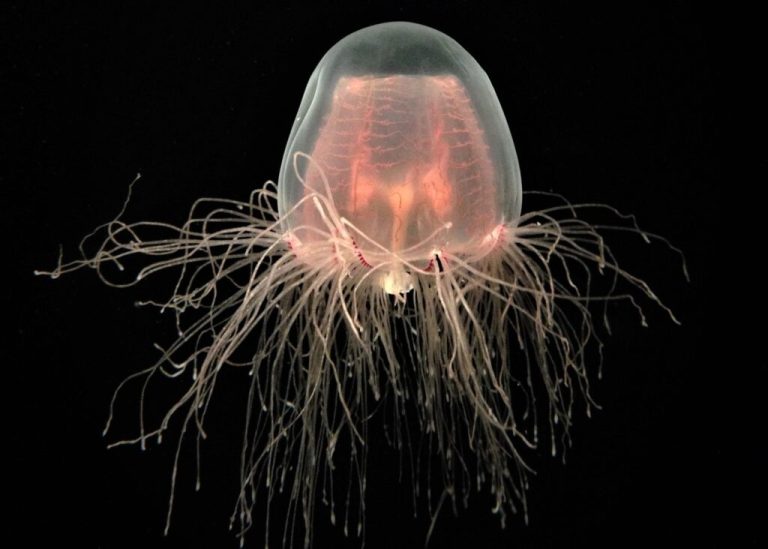

The Associated Press reports that Axayácatl flies, also known as “bird flies,” because birds eat them, resemble “water boatmen,” brownish bugs that appear to use their hind legs to row in ponds and lakes.

Today, modern farmers use the same harvesting techniques as the Aztecs, per the BBC. They hand-weave tight reed nets, then leave them floating on the water for up to three weeks while Axayácatl flies lay their eggs on top. Farmers then remove the nets from the water and leave them out to dry before preparing them for sale.

The tiny golden eggs are prized for their distinctive flavor. One way to prepare ahuautle involves mixing it with milk, chicken eggs, breadcrumbs, onion, and coriander, to prepare a batter. Then, the tennis ball-sized scoops are dropped into a pan of oil, fried to a golden brown, and flipped. The resulting pancakes are served with a sauce made of garlic, tomatillos, and serrano chiles.

Chef and restaurateur Beatriz Ayluardo told the BBC the recipe was passed down to her from her mother-in-law. “She was very passionate and knowledgeable about ancestral ingredients like ahuautle. She would make them at home and tell us stories about how they were once eaten by emperors and gods.” Ahuautle can also be served with nopal cactus and squash flowers.

While it can still be found on some restaurant menus and in kitchens around Mexico City, the tradition is under threat. One reason is that most of the eggs are sourced from Lake Texcoco. Hundreds of years ago, much of the lake was drained to make way for the capital city. Now, it’s drying up. There are also few farmers willing to do the work — around six in the Texcoco area. Awareness and interest are diminishing as well, especially among younger generations. And because supply is hard to come by, the delicacy has become increasingly expensive — about $23 per pound, according to Mexico News Daily.

Although the odds may be stacked against them, some locals are determined to keep the tradition alive. Jorge Ocampo, agrarian history coordinator at the Center for Economic, Social, and Technological Research on Agribusiness and World Agriculture in Mexico State, told the AP it’s an example of “community resistance.”

Gustavo Guerrero, who serves ahuautle at his eatery in Mexico, noted that the dish reminds him of his childhood. “Eating this is like revisiting the past,” the 61-year-old said.