“Wolves are to Yellowstone what water is to the Everglades,” Doug Smith, the former director of the Yellowstone Wolf Recovery Project and current National Park Service wildlife biologist, once said.

That sentiment is especially evident in a recent study highlighting the predators’ slow yet steady role in bringing the park’s ecosystem back into balance — all the way down the food chain, from elk populations to plants.

On Jan. 12, 1995, eight gray wolves were brought by truck from Canada to Yellowstone. They were the first to set foot in the park in about seven decades, and by the following year, their number had more than tripled. After being hunted to eradication by the end of the 1920s, the canines were reintroduced in part to help control the area’s ever-growing population of elk, which were overgrazing the vegetation. The park’s woody vegetation was “severely” damaged from the elks’ munching, an effect that has similarly been seen in Olympic National Park in Washington and Banff and Jasper National Parks in Canada.

The new study evaluated a phenomenon referred to as a “trophic cascade,” or the indirect effects of predators on a food web’s lower levels. Per the paper, trophic cascades “play a critical role in shaping ecosystems.” Focusing primarily on how wolves have impacted riparian willows, the researchers used data from 2001 to 2020 to measure the trees’ growth.

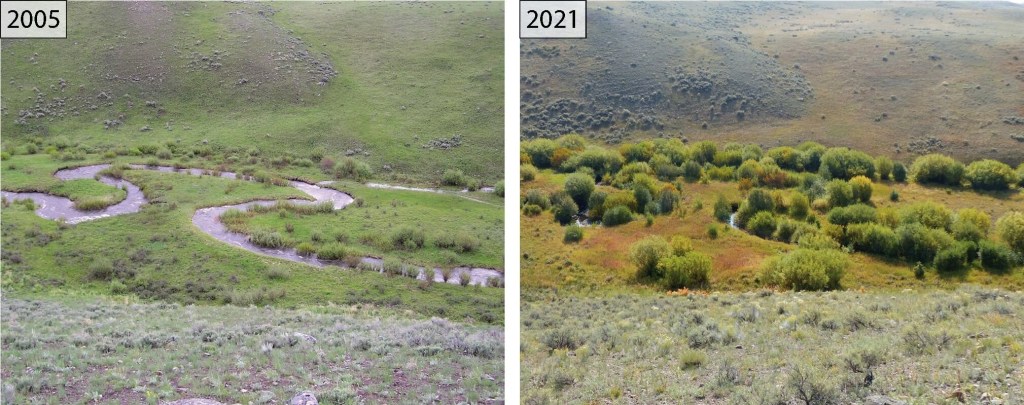

Publishing their results Jan. 14 in the journal Global Ecology and Conservation, they determined that willow volume had increased by 1,500% over the span of 20 years. As willow is a common food source for elk and elk is a primary food source for wolves, more wolves means more willow.

“Our findings emphasize the power of predators as ecosystem architects,” lead study author William Ripple said in a news release, noting the importance of abundant willow as a vital food source and habitat for birds and other animal species.

The increases in the willow’s crown volume and height indicated “a significant three-dimensional recovery,” per the statement, though the authors note that the degree of recovery varied considerably by site. Still, they explain in the study that the trophic cascade on Yellowstone was “relatively strong,” compared to other trophic cascade studies that used similar measures of analysis.

“The restoration of wolves and other large predators has transformed parts of Yellowstone, benefiting not only willows but other woody species such as aspen, alder, and berry-producing shrubs. It’s a compelling reminder of how predators, prey, and plants are interconnected in nature,” Ripple said.

These results not only provide new insight into Yellowstone’s ecosystem, but also highlight “the importance of long-term monitoring to capture gradual ecological responses following predator reintroductions,” the authors write in the study. Knowing the effectiveness of conducting studies over extended periods of time can help future researchers accurately evaluate ecosystem recovery and biodiversity outcomes.

“In the early years of this trophic cascade, plants were only beginning to grow taller after decades of suppression by elk. But the strength of this recovery, as shown by the dramatic increases in willow crown volume, became increasingly apparent in subsequent years,” said co-author Robert Beschta, an emeritus professor at Oregon State University, said in the release, noting: “Our analysis of a long-term data set simply confirmed that ecosystem recovery takes time.”