This article was originally written by Charlie Fenton for SWNS — the U.K.’s largest independent news agency, providing globally relevant original, verified, and engaging content to the world’s leading media outlets.

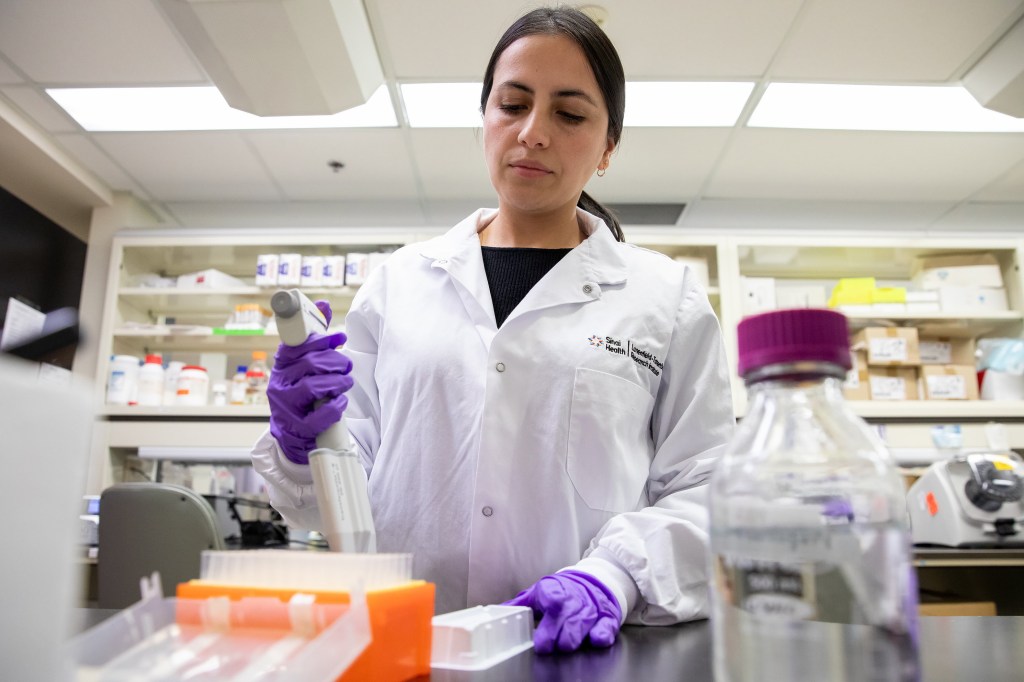

An estimated 1 million people in the U.S. have Crohn’s disease, a form of inflammatory bowel disease that causes ongoing digestive symptoms, pain, and tiredness. But that number may one day decline thanks to a simple blood test, which Canadian scientists say can not only detect the disease years before symptoms appear but also opens the doors to potential prevention.

The new test measures a person’s immune response to flagellin, a protein found on gut bacteria. Per a news release, in a healthy digestive system, different types of gut bacteria can “coexist peacefully” — but for patients with Crohn’s, the immune system launches an attack against innocuous, even beneficial, microbes.

It’s previously been shown that Crohn’s patients have elevated levels of flagellin antibodies, so the research team sought to determine whether these antibodies were also present in healthy individuals who are at risk of developing the disease.

“We wanted to know: Do people who are at risk, who are healthy now, have these antibodies against flagellin?” lead author Ken Croitoru, a clinician scientist with Mount Sinai Hospital’s Center for Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Toronto, explained. “We looked, we measured, and yes indeed, at least some of them did.”

To come to their conclusions, he and his colleagues evaluated 381 first-degree relatives of Crohn’s patients. Seventy-seven people in that group later went on to develop the disease, and 28 had elevated antibody responses prior to being diagnosed. The responses were strongest in siblings, highlighting the role of shared environmental exposure.

Per the research team, the findings suggest that the immune reaction may help trigger the onset of the disease, rather than being a consequence of it.

The results also showed that this pre-disease response to the flagellin was linked to intestinal inflammation and gut barrier dysfunction, which are both characteristics of Crohn’s disease. The typical timeline from blood sample collection to the pre-disease individuals being diagnosed with Crohn’s was nearly two and a half years.

The research is part of the Genetic, Environmental, and Microbial Project, which collects genetic, biological, and environmental data to understand how Crohn’s develops. It involves more than 5,000 healthy first-degree relatives of people with the disease around the world and has given researchers a rare opportunity to study the earliest pre-disease stages. So far, 130 participants have developed Crohn’s.

A better understanding of the early immune process that the new study focused on could pave the way for novel methods of predicting, preventing, and treating the disease. “With all of the advanced biologic therapy we have today, patients’ responses are partial at best,” Croitoru said. “We haven’t cured anybody yet, and we need to do better.”

Co-author Sun-Ho Lee noted that the study results “increase the possibility of designing a flagellin-directed vaccine in selected high-risk individuals for prevention of disease. Further validation and mechanistic studies are underway.”

RELATED: New Blood Test More Accurately Predicts Risk of Heart Attack, Stroke