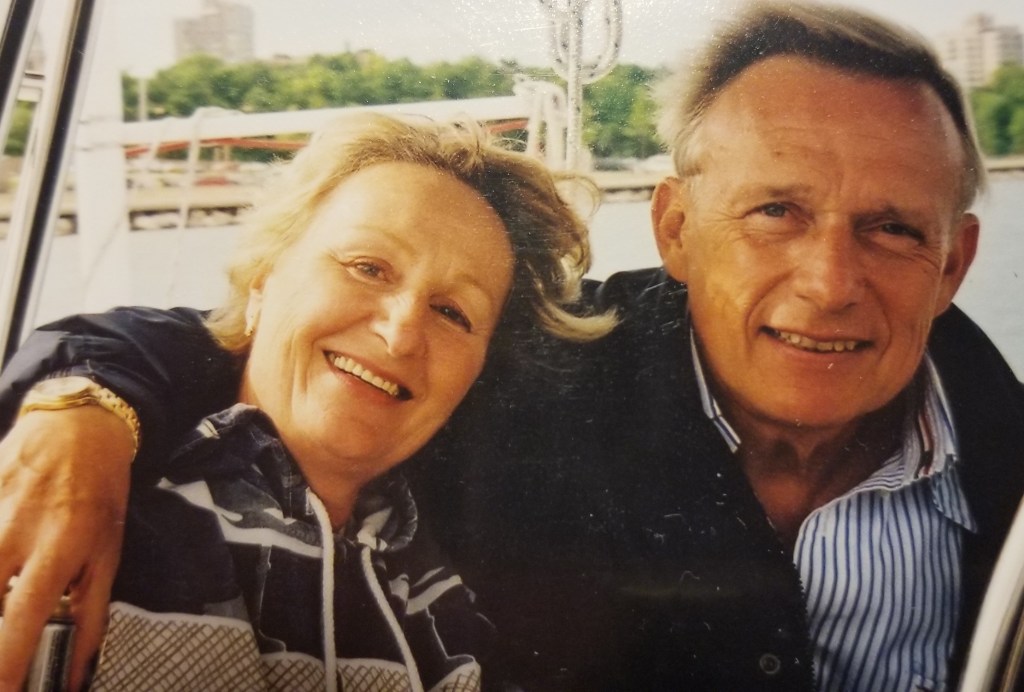

When Martin J. Schreiber first ran for public office in 1962, his wife, Elaine, was his hardest working campaigner and biggest support system. She was there for him in subsequent elections whether he won or lost, and stood proudly by when he became the 39th governor of Wisconsin in 1977. In later years, Elaine remained a source of strength for Martin as he transitioned from politics to a career in public affairs, even as she went back to college and earned a master’s degree at age 56.

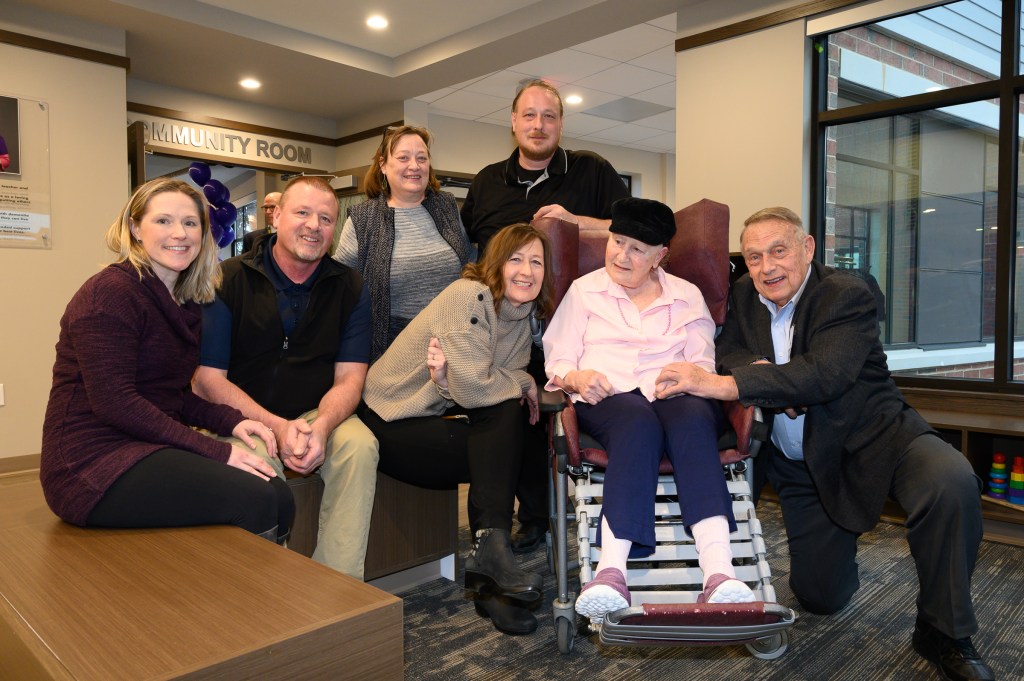

But when Elaine was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in the mid-2000s, their roles began to reverse, and Martin gradually found himself in the position of caregiver. As her disease progressed, he realized the woman he’d raised four kids with, who’d been by his side for nearly six decades, was slipping away, and another person was emerging in her place — one Martin didn’t recognize.

“The first Elaine, that was the wonderful girl I met when I was a freshman in high school in Latin class,” he told Nice News, adding that she was “my friend, my advisor, my companion, everything that you could ever want in a life partner.” He shared that “the second Elaine” began to appear when his wife was 63. “She began to get lost driving to and from places she had been going to and from for 10 years. She would come up with stories about things that happened and they never occurred.”

In his book, My Two Elaines: Learning, Coping, and Surviving as an Alzheimer’s Caregiver, now out in paperback, Martin writes about his experience caring for Elaine, which he did for nearly 20 years from her diagnosis to her death in 2022. He also explains in poignant detail what it was like to grieve someone who was still alive, and offers advice for other caregivers.

“I think one of the things that is most important for caregivers and friends of the person who’s ill is to understand that if Alzheimer’s is bad, ignorance of the disease is worse,” said Martin.

“That’s really why I wrote the book,” he added. “When the doctor told me that Elaine had Alzheimer’s, I tried to figure out ‘How can I deal with this?’ So I went to the bookstore and there were any number of books on Alzheimer’s, but I found nothing that gave me an insight into the kind of guidance that a caregiver would need.”

Read on for some of the insight he gleaned from his own experience.

Advice for Other Caregivers

Therapeutic Fibbing

When a person has Alzheimer’s, their reality differs from everyone else’s, and one of the early mistakes Martin found himself making in his interactions with Elaine was trying to force her to join his world rather than him joining hers.

“As long I tried to keep Elaine in my world — ‘Elaine, it didn’t happen on a Thursday. It happened on a Friday.’ ‘Elaine, it wasn’t the Smiths, it was the Joneses.’ ‘Elaine, why did you put the car keys in the dishwasher?’ ‘Elaine, I told you 10 times, you’re leaving at five’ and so forth — that was a great mistake on my part,” he recalled, noting that constant corrections like these tend to cause undue distress for both parties, without any real pay-off.

Instead, he recommends practicing “therapeutic fibbing.” In the book, which he penned with Milwaukee-based writer Cathy Breitenbucher, Martin explains a pivotal moment when he realized he’d been placing too much value on Elaine understanding what is and what isn’t.

“I once made the terrible mistake of answering one of Elaine’s questions about her parents by telling her the truth, that they were dead. She looked as sad as the day many years earlier when she’d learned that they had died,” he writes, adding, “Until I saw the sorrow in her eyes, I didn’t know that the truth wasn’t always relevant. I vowed I wouldn’t put her through that kind of pain again.”

Unacknowledged Grief

Martin said one thing many Alzheimer’s caregivers don’t realize, and thus cannot process, is that they’re actually grieving.

“I had a friend, 79 years old, and he had a heart attack, bang, gone. And it was a tragedy. But there was a funeral and friends came by to express their condolences. And there was closure,” Martin shared. “A person who’s a caregiver sees their loved one pass away a little bit every day. We morph from being a loving, caring spouse or partner into being a caregiver. And in that morphing process, we don’t know that we are also carrying this grief.”

By dealing with that “unacknowledged grief,” whether with the help of counseling or through personal reflection, caregivers can experience some relief from their pain, he said.

“I think to get that kind of exposure, you know, it’s sort of like lancing a boil and just, ‘I now understand one of the reasons I feel so terrible. And yes, I can cry, I should cry.’”

Caring for Yourself

When Elaine first started showing symptoms around 22 years ago, the disease could not be cured or prevented. Today, the same is true.

“We can’t win a battle with Alzheimer’s,” Martin said, adding, “[What we can do] is make a determination to help our loved ones live their best lives possible. And there’s two parts to this. One is by helping them live their best lives possible, but also — helping ourselves as caregivers live our best lives possible. Because if we don’t, we’re useless.”

He called caregivers “lifelines” to their loved ones, and pointed out that by not getting enough sleep, not eating right or exercising, not socializing, they can cause that lifeline to wither away: “We become not only irrationally irritable, but it also destroys our psyche and our strength, thereby taking away our ability to help the person we love the most.”

Asking for Help

“To ask for help is a matter of courage,” Martin insisted, and doing so is crucial when you’re feeling like you don’t have the time or energy to care for the person you love. He recommended calling the Alzheimer’s Association 24/7 helpline, which you can find at the end of this article, as well as reaching out to local resources.

“Many communities have Alzheimer’s support groups,” said Martin. “It may take a little bit of digging, but they’re there, believe me.”

He added that men, in particular, may benefit from a mindset shift around reaching out for help.

“Understand that this idea of not asking for directions, that’s sort of a goofy kind of thing going back to the Dark Ages, and my friends, let’s get with it,” he said. “This disease is something that, you have to understand, you can’t do it alone.”

How to Support a Caregiver

Acknowledge Their Challenges

Validating what a caregiver is going through is immensely valuable, Martin stressed.

“One of the most important things you can do for a caregiver is simply acknowledge the fact that [they’ve] got one of the toughest jobs that ever was created,” he said. “And that simple acknowledgement is going to go a long way in making a difference in the whole attitude of the caregiver.”

Take Specific Action

Rather than telling your friend or relative who is caring for someone with Alzheimer’s to call you if they need help, go ahead and offer up a specific action you can take off their plate.

“Say, ‘I will pick up the prescriptions for you at such and such a time,’ or ‘I will come by with a meal at such and such a time,’ or ‘I will stop by and take your loved one for a walk,’” he suggested.

“And what you’re doing then is you are [not only] helping hearts touch, but you are giving the caregivers some relief, some respite to allow them to rekindle their energies and then in turn, be a better caregiver.”

Alzheimer’s Isn’t a “Chicken Casserole Disease”

Before the end of our interview, Martin stressed that Alzheimer’s isn’t “what you call a ‘chicken casserole disease,’” and explained that when someone has surgery or breaks a hip, others know without asking to do things like drop off a chicken casserole, for example.

“People understand broken hips and they understand heart operations, but they don’t understand Alzheimer’s,” he said, noting that “friends of 25, 30, 40 years” end up doing nothing — not because they’re cold or cruel, but because they simply don’t know what to do.

“Now not only is the caregiver going through this horrible prognosis, this unacknowledged grieving, the worry, the anxiety, everything that goes with it. But also you get the feeling of being deserted, of being abandoned by your friends.”

If more people were intentional about educating themselves on all aspects of Alzheimer’s, “they’d be able to really bring more moments of joy into people’s lives,” Martin said. “And what better thing could we do than that?”

Helpful Resources

Alzheimer’s Association

24/7 Helpline: 1-800-272-3900

National Institute on Aging

(Includes information on adapting activities for people with Alzheimer’s; caring for yourself; and getting help)