Smell is one of the most powerful, and complicated, of the five senses. Olfaction has been linked to memory, cognition, and mood, and may even influence our other senses as well. So losing the capability, a condition known as anosmia, is not only frustrating and inconvenient, but can also be extremely emotionally taxing. That’s why two researchers at the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine are developing a neuroprosthetic — what they call a “bionic nose” — that will help those experiencing partial or complete loss of smell.

Richard Costanzo, director of research for the VCU Smell and Taste Disorders Center and recipient of a career achievement award for his decades of work in the field, has been pioneering olfactory research since 1979. He and Daniel Coelho, a surgeon and professor of otolaryngology, are developing the device, and they expect to have a fully functioning prototype within the next five to 10 years, The Washington Post reports.

Several medical issues can lead to anosmia, including brain injuries and diseases that damage olfactory cells. And due to COVID-19, even more individuals are currently struggling with the condition. Per Healthline, at least 27 million people worldwide experienced loss of smell or taste due to the virus, and some still haven’t gotten the sense back. In May of 2022, Costanzo and Coelho surveyed 267 adults who lost their smell in 2020 due to the illness, and found that in 7.5%, the condition still persisted two years later.

But because the olfactory system is so complex, instruments comparable to those created for problems with other senses, like eyeglasses or hearing aids, aren’t commercially available for people with anosmia.

“The problem with smell is that we don’t know what physical properties of chemical odors are important for encoding all the different smells that exist,” Costanzo told the Post.

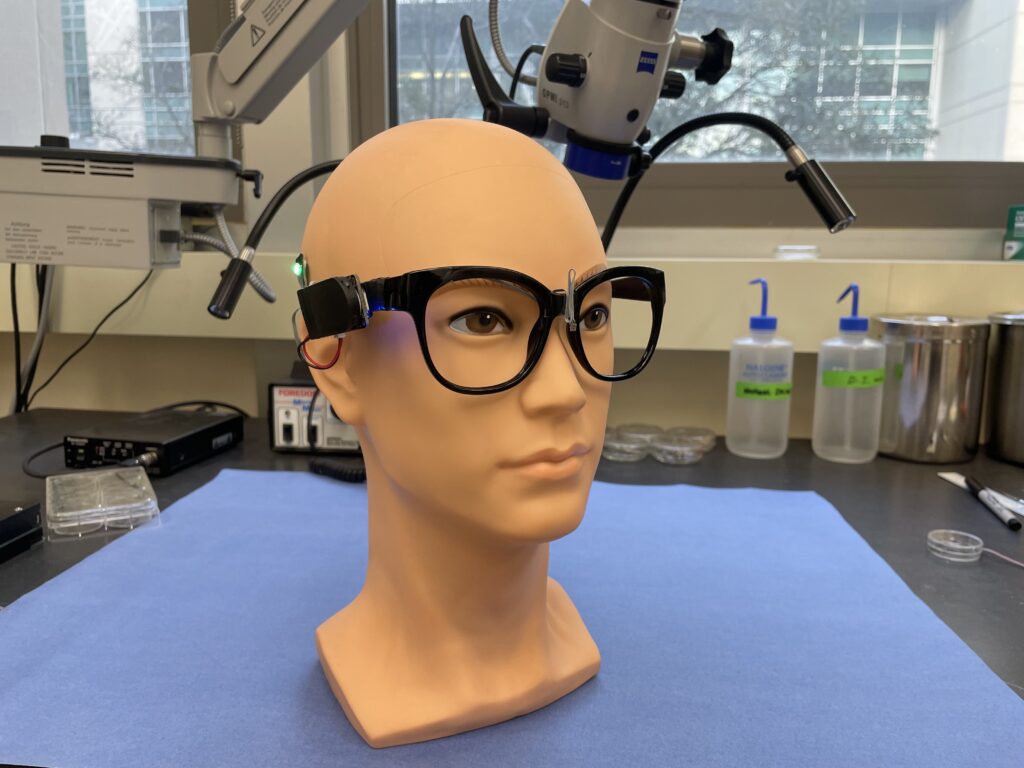

To combat this, he and Coelho’s bionic nose relies on computer processing and artificial intelligence. The device features an external sensor, attached to a pair of glasses, that communicates with an internal microprocessor chip. The chip then creates “unique digital fingerprints for different smells,” explained Costanzo, and sends the information to a receiver implanted in the wearer’s skull, which generates the perception of smell.

Speaking to IEEE, Coelho likened the tool to a cochlear implant: “It’s taking something from the physical world and translating it into electrical signals that strategically target the brain,” he said.

And though the neuroprosthetic is still years away from being able to be purchased, Costanzo said he receives encouragement from some of the people he hopes will one day benefit from his work. “They’re so appreciative that someone is working on a solution,” he told the outlet.

“Hope is coming,” Coelho elaborated in the Post. “There are a few important things that we need to get into place, but there’s very little reason to think that this device shouldn’t work.”