This article was originally written by Stephen Beech for SWNS — the U.K.’s largest independent news agency, providing globally relevant original, verified, and engaging content to the world’s leading media outlets.

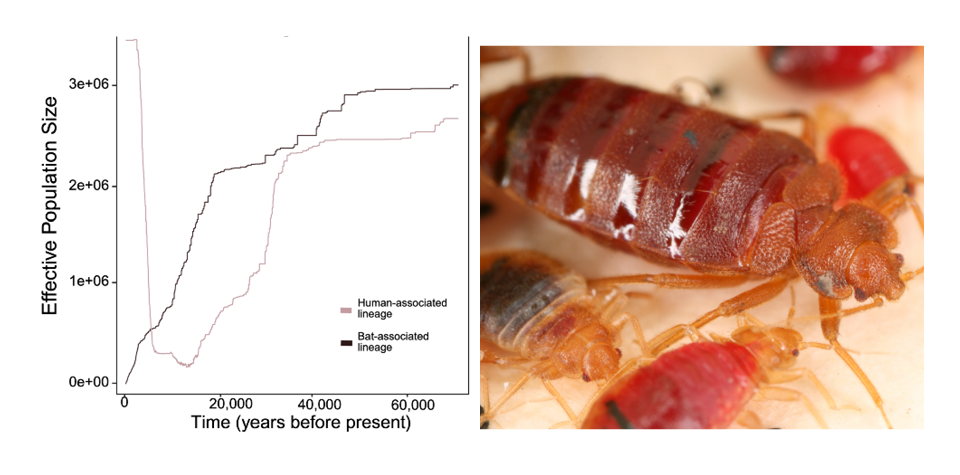

Our planet is home to around 1 million known insect species, and about 1%-3% of them are considered pests, per the National Pesticide Information Center. But which one has been bugging humans the longest? A team of scientists led by two Virginia Tech researchers think they’ve figured it out: In a study published Wednesday, they suggest that bed bugs were the first human pest.

The bugs began their pesky relationship with people when they hopped off a bat and attached themselves to a Neanderthal around 60,000 years ago, the authors say — and they’ve stuck around their human hosts ever since.

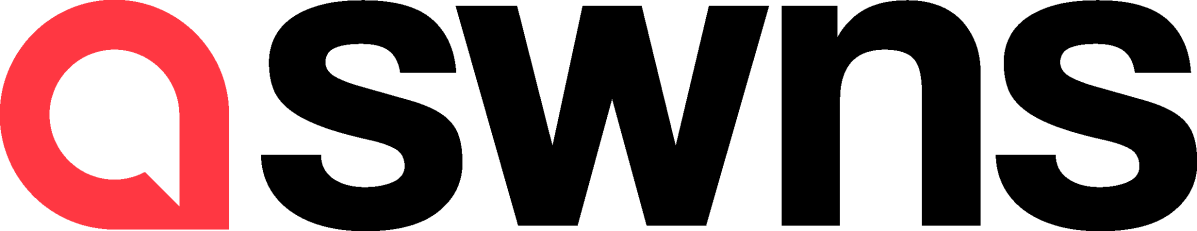

But according to the researchers, the populations of bed bugs that stayed with bats have been declining since the Ice Age, also known as the Last Glacial Maximum, around 20,000 years ago.

The team compared the whole genome sequence of the two genetically distinct lineages of bed bugs: those associated with bats and those with humans. Their findings indicate that the human-associated lineage followed a “similar demographic pattern” as humans, meaning bed bugs may well be the first true urban pest.

“We wanted to look at changes in effective population size, which is the number of breeding individuals that are contributing to the next generation, because that can tell you what’s been happening in their past,” study co-lead Lindsay Miles said in a news release.

By studying the historical and evolutionary symbiotic relationship between humans and bed bugs, scientists may be able to generate future models that predict the spread of pests and diseases under urban population expansion, and identify the traits that co-evolved in both humans and pests.

“Initially with both populations, we saw a general decline that is consistent with the Last Glacial Maximum; the bat-associated lineage never bounced back, and it is still decreasing in size,” Miles said. “The really exciting part is that the human-associated lineage did recover and their effective population increased.”

She referenced the early establishment of large human settlements that expanded into cities like Mesopotamia around 12,000 years ago. As the human population increased and continued living in communities and cities expanded, the human-associated bed bug lineage’s population size experienced an “exponential” growth.

“That makes sense because modern humans moved out of caves about 60,000 years ago,” said study co-lead Warren Booth. “There were bed bugs living in the caves with these humans, and when they moved out, they took a subset of the population with them so there’s less genetic diversity in that human-associated lineage.”

By using the whole genome data, the researchers now have a foundation to continue studying the 245,000-year-old lineage split.

Since the two lineages have some genetic differences, yet not enough to have evolved into two distinct species, the researchers want to focus on comparing the evolutionary alterations that have taken place more recently.

“What will be interesting is to look at what’s happening in the last 100 to 120 years,” said Booth. “Bed bugs were pretty common in the old world, but once DDT was introduced for pest control, populations crashed. They were thought to have been essentially eradicated, but within five years they started reappearing and were resisting the pesticide.”

In a previous study, the research team discovered a gene mutation that could contribute to that insecticide resistance — and now, they’re looking further into bed bugs’ genomic evolution and its relevance to the pest’s insecticide resistance. Concerned about the itty-bitty critters taking up residence in your space? Follow these at-home tips to prevent or get rid of bed bugs.

RELATED: New Research on Ticks May Lead to Better Vaccines — Here’s How to Prevent Bites in the Meantime