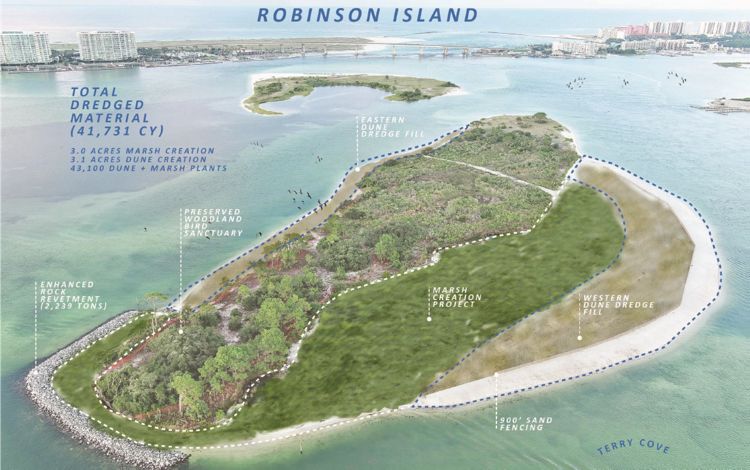

Three undeveloped barrier islands off the coast of Orange Beach, Alabama, are havens for a diverse array of wildlife — and after an eight-year-long, nearly $13 million project following years of storm damage, 30 acres of habitat have been restored. The Lower Perdido Islands near Perdido Pass are also hot spots for boaters, and now, wildlife and human visitors can continue enjoying the sandy beaches for decades to come.

“These islands are really important to the community of Orange Beach, with their pristine scenery and abundant marine life,” NOAA Marine Habitat Resource Specialist Stella Wilson said in a press release. “Our goal is to increase the longevity and resilience of these habitats into the future.”

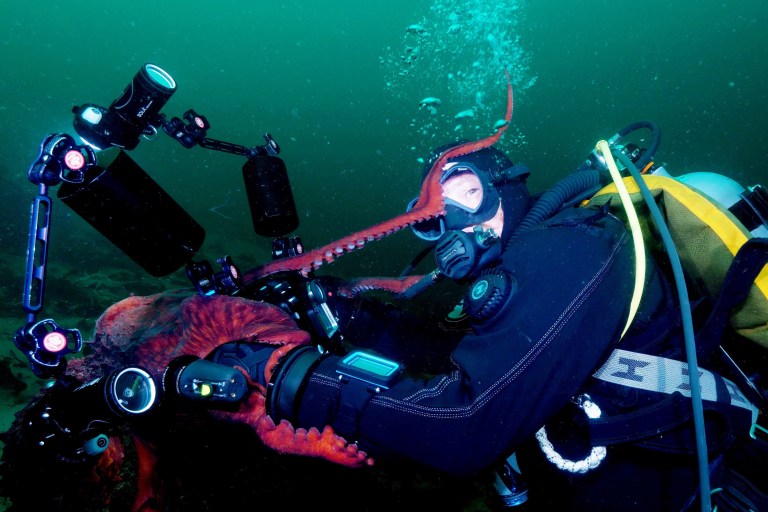

Though small in size, the islands are “ecologically rich,” according to the NOAA. During peak migration, up to 30 million birds can fly over Robinson, Bird, and Walker Islands in one night. The area on and around the isles also features marsh, forest, and seagrass habitats that host a plethora of wild animals: Birds like tricolored herons, snowy egrets, and brown pelicans forage there, along with marine creatures like redfish, blue crabs, and speckled seatrout.

In addition to boasting lush ecosystems, the islands act as “speed bumps” to help protect inland communities from storms, explained Katie Baltzer, coastal project manager for The Nature Conservancy. “They slow the wave energy down and provide some protection against storm surge to the surrounding community,” she told the NOAA. “If those islands weren’t there, everything would be moving a little bit faster.”

But the birds aren’t the only ones that enjoy the islands: Upward of 8 million people visit them and the surrounding turquoise waters every year, with over 500 boats parking along the sandy white shores during holidays — and those numbers are only going up. And due to multiple factors, including the influx of visitors, years of storms, the 2010 Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill, and erosion, the islands have begun to shrink. “The island system is at risk of being loved to death,” said Baltzer.

So in 2017, the Conservancy partnered with several organizations, including the City of Orange Beach, to devise a plan that would protect the islands while maintaining their stunning beaches for human recreation. In a project that commenced this past January and was funded by NOAA’s Office of Habitat Conservation and the Deepwater Horizon Alabama Trustee Implementation Group, a team of ecologists and engineers installed sediment, implemented a protective sand dune, reinforced revetment, and planted over 200,000 native plants.

On Walker Island — a designated bird sanctuary that will remain closed to the public — the team designed two restoration placement areas to expand wildlife habitats. They also implemented no-motor and no-wake zones to help protect seagrass beds, which are declining globally but have been expanding around all three islands for more than two decades.

“It was a huge undertaking,” Baltzer said. “But we wanted to make sure the seagrass beds could keep expanding, not shrink. It’s a core part of the ecosystem here.”

While Robinson and Bird Islands are open to visitors, certain sections of the former are protected to create distance between humans and birds.

“We want to highlight how important and sensitive these areas are,” said Deepwater Horizon Natural Resource Damage Assessment team lead Erin Plitsch. “We’re making more room for wildlife to feel at home, and visitors can help by giving them a little space too — it’s a simple way to be part of something really meaningful.”

RELATED: “The Power of Predators”: How Wolves Helped Restore the Ecosystem in Yellowstone National Park