The ubiquitous Swiss Army knife was first invented in the late 19th century, but humans have been using and sharing similar multipurpose tools for much, much longer.

Sixty-thousand to 70,000 years ago, Homo sapiens ventured out of Africa, eventually landing in Asia, Australia, Europe, and the Americas. While that migration was not the first, scientists believe it’s the greatest demonstration of our ancestors’ ability to settle in and adapt to vastly different biomes. Now, exciting findings from a team of archaeologists suggest that ancient knives indicate social connectivity, which may have significantly helped early humans spread out and prosper across the globe.

A group of researchers helmed by Dr. Amy Mosig Way of the University of Sydney and the Australian Museum points to a key reason the members of that African diaspora thrived. Analysis of 65,000-year-old “stone Swiss Army knives” shows for the first time that shared knowledge across groups of people was a crucial component of our ancestors’ success.

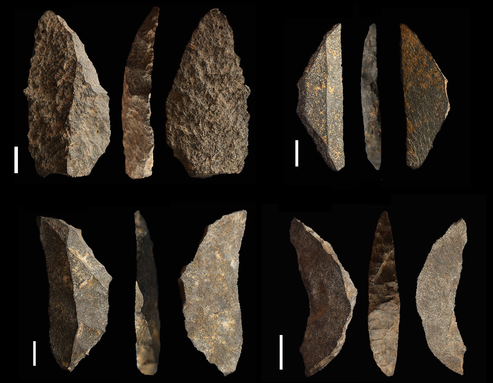

The team, who published their findings in Scientific Reports this June, analyzed small tools known as “backed artifacts” — sharp blades that were most likely inset within another material. The blades were found throughout seven sites in southern Africa and were used for hunting and cutting. Made during Howiesons Poort, a roughly 5,000-year time period within the Middle Stone Age, the tools represent an era marked by striking technological and cultural innovation.

“The really exciting thing about this find is that it gives us evidence that there was long-distance social connection between people, just before the big migration out of Africa, which involved all of our ancestors,” Way told The Guardian. The seven locations where the tools were found represent a distance of 1,200 km (about 745 miles) and a variety of ecological niches. “One hundred kilometers takes five days to walk, so it’s probably a whole network of groups that are mostly in contact with the neighboring group,” Way said.

Because the blades had to be attached to handles using glue and adhesives, which was a complicated process, the sharing of complex information is likely. The tools also suggest growing “cultural affiliation” between groups in different locations, the study notes.

Many artifacts of that era, including etched ostrich eggshells and engraved ochre, are thought to have largely symbolic significance. Archaeologists previously theorized that gift-giving and trading might account for the proliferation of these tools across the continent, but Way’s team discovered the materials used to create the ancient knives were local to each site, suggesting social connectivity by way of shared knowledge rather than shared tools.

The findings have exciting implications in the global scientific community, as they shed further light on the early interconnectedness of humanity.

“Examining why early human populations were successful is critical to understanding our evolutionary path,” Professor Kristofer Helgen, Chief Scientist at the Australian Museum, said in a news release. “This research provides new insights into our understanding of those social networks and how they contributed to the expansion of modern humans across Eurasia.”