It turns out we have tiny architectural experts scuttling through our parks, sidewalks, and backyards — and they may have a few things to teach us about how to prevent the spread of disease. The designers in question are ants, already known for their mighty strength, thriving social lives, and mind-boggling ability to build entire underground cities. And in a recent study out of the University of Bristol, researchers identified the insects as the first-known social species other than humans to alter their social spaces to combat disease transmission.

“We already know that ants change their digging behavior in response to other soil factors, such as temperature and soil composition,” lead author Luke Leckie said in a press release. “This is the first time a non-human animal has been shown to modify the structure of its environment to reduce the transmission of disease.”

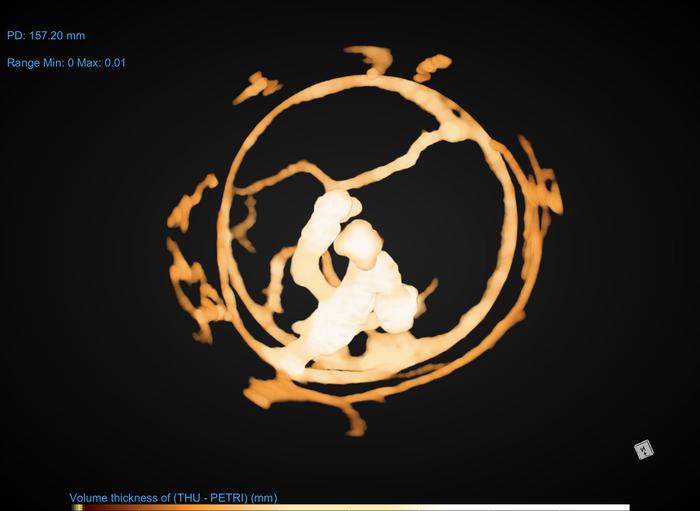

A micro-CT scan of an ant colony

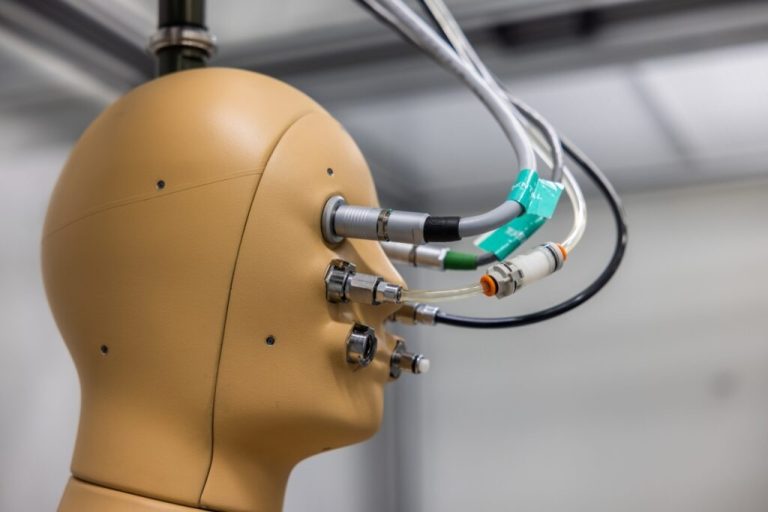

To figure this out, the team introduced two groups of 180 black garden ants to containers filled with soil, and gave them one day to begin forming their nests. Then they added 20 ants to each nest, having previously exposed one of these groups to spores of Metarhizium brunneum, a disease-causing fungus. Over the following six days, the researchers used a 3D-scanning technique called micro-CT to compare how the healthy and infected ants dug their nests.

Their findings? The insects exposed to the fungus made several architectural changes: They expanded their nests more quickly, widened the gaps between entrances, and lengthened travel routes, which helped separate healthy and diseased individuals, even at the cost of efficiency. All of these modifications were found to minimize transmission and protect areas where young ants and food stores were kept. According to the authors, the changes “highlighted a synergy between architectural and behavioral responses to disease.”

Princeton University evolutionary biologist Sarah Kocher, who wasn’t involved in the study, told NPR, “Instead of relying on their individual immune systems, they work together as a group to try to minimize disease spread and utilize ways that their collective behaviors can help to defend them against these diseases.”

This isn’t the first time ants have been observed banding together to protect their peers from infection. A 2016 study found that fungus-growing ants covered eggs, pupae, and larvae in the same benign fungus they cultivate for food because the practice helps protect the young insects from Metarhizium brunneum.

A 2018 study also demonstrated that “nurse” ants, which care for the queen and younger individuals, distanced themselves from foragers, which are more at risk of becoming infected, after a disease-causing fungus was introduced. “Mortality was higher among foragers than among nurses,” study co-author Nathalie Stroeymeyt, who was also involved in the recent research, said in a news release at the time. “And all the queens were still alive at the end of the experiment.”

While Stroeymeyt told NPR she believes the new findings are “too ant-like to have direct application today,” they open the door to further research on how our own social spaces can be designed and managed to prevent the spread of disease. She said: “We can learn from social insects, which have evolved over millions of years, to find strategies that balance this protection against epidemic without completely disrupting the functioning of the entire colony.”