On May 9, Ecuador’s record-breaking “debt-for-nature” deal made history: The country sold $1.6 billion worth of bonds to the bank Credit Suisse, which freed up funds that will be used for conservation of its renowned Galapagos Islands. This marked the world’s largest “debt-for-nature” swap to date.

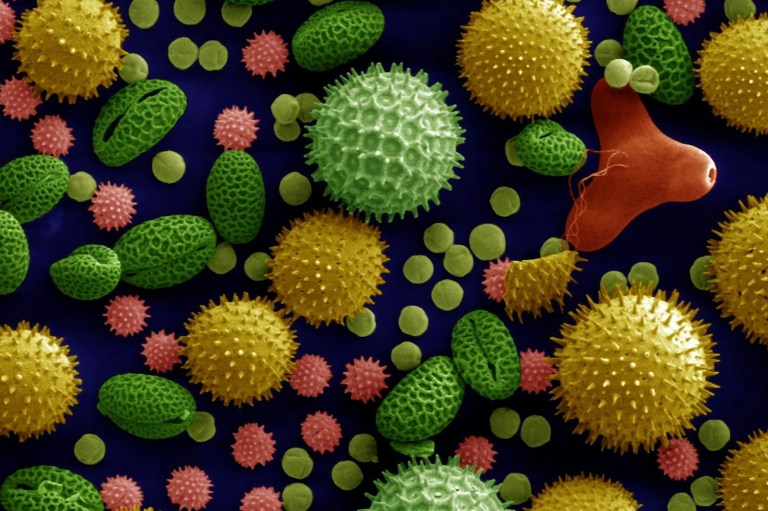

The Galapagos Islands is an archipelago celebrated for its wealth of distinct flora and fauna. Many Galapagos species — including its giant tortoises and marine iguana — exist nowhere else on the planet, Euronews reports. It was here that Charles Darwin, in the course of his travels, first encountered various species that would prove pivotal in his development of the theory of natural selection. Reflecting on this illustrious history, Ecuador’s foreign minister, Gustavo Manrique Miranda, observed that his country was equally rich to the wealthiest in the world, “but our currency is the biodiversity,” per The New York Times.

While the size of the deal was historic, it’s not the first of its kind. So how do these kinds of deals work, and why are they important?

What’s a debt-for-nature deal?

Debt-for-nature transactions began in the 1980s and are described as being “a bit like refinancing a mortgage, only for government bonds,” according to The New York Times. Countries experiencing financial difficulties often sell bonds, which are repaid over time with interest.

In the case of Ecuador, the country is currently grappling with significant debt and political turmoil. Consequently, its bonds have lost tremendous value on the market, which resulted in some investors selling approximately $1.6 billion worth of them to the bank Credit Suisse for roughly 40 cents on the dollar in an attempt to cut their losses, per The Times. Credit Suisse has since converted those bonds into a $656 million Galápagos Marine Bond that will be used to “finance a loan that will help Ecuador fund conservation.”

This arrangement will save the South American country more than $1 billion, both in interest and principal payments, while previous bondholders avoid potentially bigger financial losses.

“The new loan will be repaid over the next 18 years with the country providing around $17 million (€16 million) a year for conservation,” Euronews explains. “Once the payments from Ecuador finish in 2040, it says assets from stable investment and repayment should be enough to continue funding conservation at the same level in perpetuity.”

Who else has entered into these deals?

During the COVID-19 pandemic, when lockdowns devastated economies, debt-for-nature transactions gained significant traction, per The Times. Countries like Belize, Barbados, and Seychelles have entered into such arrangements in recent years, with each deal already proving successful.

In 2022, Virginia nonprofit The Nature Conservancy lent Belize over $350 million to buy back international bonds, which freed up more than $200 million for the Central American country to spend elsewhere. As part of the deal, Belize agreed to protect 30% of its waters and to spend $4.2 million annually on preservation efforts in those areas, The Times reported in November. That loan was also financed by Credit Suisse. The Nature Conservancy entered into a similar debt conversion deal with Barbados a few months prior.

Options beyond debt-for-nature

There are other avenues beyond the debt-for-nature exchange. According to the World Economic Forum, other scalable models are available in the arena of climate finance. Both Chile and Uruguay “recently issued the world’s first sovereign sustainability-linked bonds,” which are directly linked to meeting climate targets.

“Debt-for-climate swaps and debt-for-nature swaps seek to free up fiscal resources so that governments can improve resilience without triggering a fiscal crisis or sacrificing spending on other development priorities,” explains the International Monetary Fund. “Creditors provide debt relief in return for a government commitment to, say, decarbonize the economy, invest in climate-resilient infrastructure, or protect biodiverse forests or reefs.”

The United States Department of Agriculture offers a variation of such a deal, known as the Debt For Nature Program or Debt Cancellation Conservation Contract Program, allowing eligible landowners who have Farm Service Agency (FSA) loans secured by real estate to cancel a portion of their FSA loan in exchange for entering into a conservation contract.

The benefits of debt-for-nature deals

Admittedly, there are challenges inherent in this newer world of environmental finance. “You can’t conserve everything and leave us with nowhere to work,” Belizean fisherman Ian Palacio pointed out to The New York Times last year. But many economists, politicians, and conservationists involved in such deals agree that conflicts of interest can be managed in a way that, with effort, will produce win-win results.

Pablo Arosemena Marriott, Ecuador’s minister of economy and finance, said, “This strategy decreases public debt, boosts fiscal stability, and creates opportunities to address basic needs like healthcare and education,” according to Euronews.

Furthermore, debt-for-nature deals provide countries with a sense of relief and inspiration. “It gave us breathing space,” Belize’s Prime Minister Johnny Briceño told The Times. “Instead of bondholders, we will now be paying to protect our environment.”

Briceño’s statement captures the win-win nature of such transactions: With loan repayments going to nature preservation instead of creditors, countries in debt not only improve their own financial futures, they also simultaneously engage in acts of service to the planet that offer the possibility of an improved future for all of humanity.