Reginald Dwayne Betts has always been into books. As a kid, he was once caught reading Sherlock Holmes stories in the back of class, and at home he’d watch an oft-played speed reading infomercial with fascination. Determined to become a speed reader himself but unable to afford the advertised course, he found an instructional guide on the subject at the public library.

It would be the last book he’d check out before entering a correctional facility. Betts was 16 years old when he and a friend used a pistol to carjack a man in Fairfax, Virginia; he confessed shortly after his arrest and was sentenced to nine years in prison. Behind bars, reading became a lifeline — and not just for him. While in solitary confinement, he learned his fellow inmates had developed an “underground library,” using torn bed sheets to devise a pulley system for passing volumes between cells.

“We go to literature because we know that we can’t know enough people, because we can’t go to enough places, because we need more knowledge about literally the way things are. But also we go to literature because we want to know ourselves better,” Betts, now 45, told Nice News, adding: “I think books offer a map to becoming that’s hard to imagine without one.”

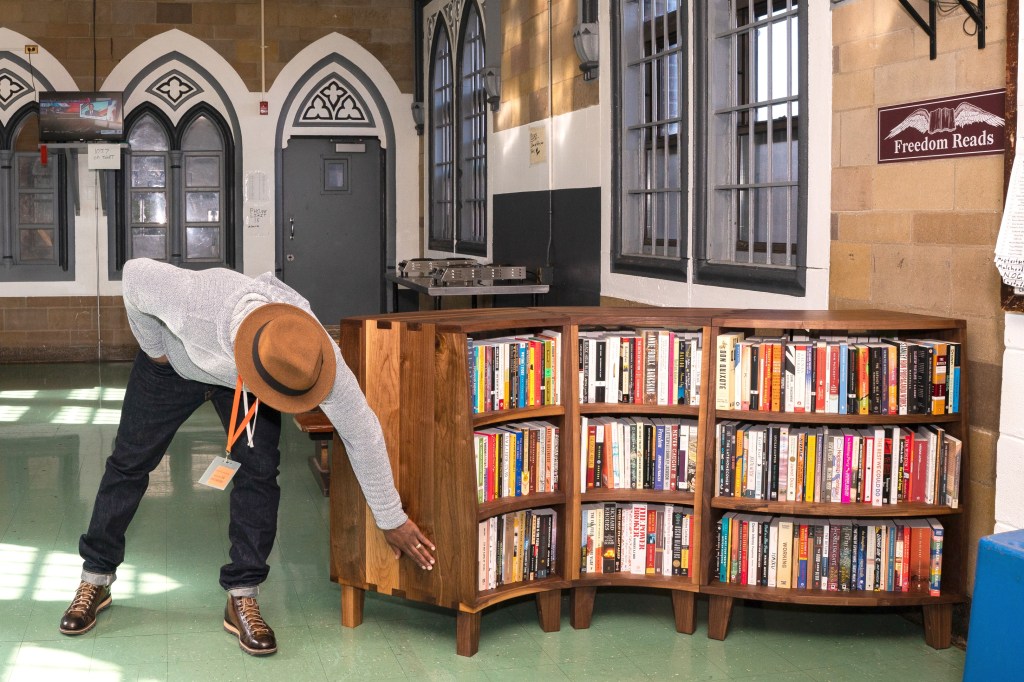

He was released in 2005, and today, Betts is an award-winning poet who holds a law degree from Yale. He’s also the founder and executive director of Freedom Reads — a nonprofit that brings handcrafted, fully stocked bookcases into prison cell blocks all over the country.

Dubbed “Freedom Libraries,” the bookcases contain 500 diverse fiction and nonfiction titles by authors like James Baldwin, Toni Morrison, Kurt Vonnegut, Min Jin Lee, J.R.R. Tolkien, and Margaret Atwood. Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst, by Robert Sapolsky, is included, as is The Black Poets by Dudley Randall, the book that inspired Betts to start writing poetry in prison at 17. Around 15% of the titles are in other languages, some with accompanying English translations, some without.

“It’s a hodgepodge,” he explained of the collection, sharing that the number 500 was inspired by the fact that Sir Walter Raleigh wrote The History of the World using the 500 books he had access to while imprisoned in the London Tower. “[We] used it as a metaphor of what you could do while incarcerated, and how you could incarcerate the body but not the brain.”

Betts hears firsthand from the men and women who benefit from the Freedom Libraries. Some send in letters “talking about how it’s changed their perspective about the world,” he said. “We once had a mom write us saying how her son had a light in his voice that he hadn’t had in years because of the interaction that he had with the Freedom Library and me and my team.”

When the project started, Betts desired a clear metric by which to measure its success. “I wanted to do it in such a way where I had some kind of center of gravity, some kind of North Star,” he explained, adding: “And we decided that that North Star would certainly be joy.”

He uses that guiding principle to drive his decision-making. Freedom Reads employs previously incarcerated people to help hand-build the libraries, providing stability and income that are otherwise hard to come by. To bring nature and beauty into the prisons, each bookcase is made of solid wood — like maple, oak, and walnut — rather than plastic. They’re also short, curved, and accessible on all sides, inviting conversations to take place over and around them.

“The library is a physical intervention into the landscape of plastic and steel and loneliness that characterizes incarceration,” the nonprofit’s website states. “In an environment where the freedom to think, to contribute to a community, and even to dream about what is possible is too often curtailed, Freedom Reads reminds those inside that they have not been forgotten.”

To date, Freedom Reads has installed 605 libraries at 60 adult and youth prisons across the country. Donate here.

RELATED: The Donation Collection Gives Formerly Incarcerated Individuals — and Fallen Trees — a Second Chance

When you buy books through our links, Nice News may earn a commission, which helps keep our content free.