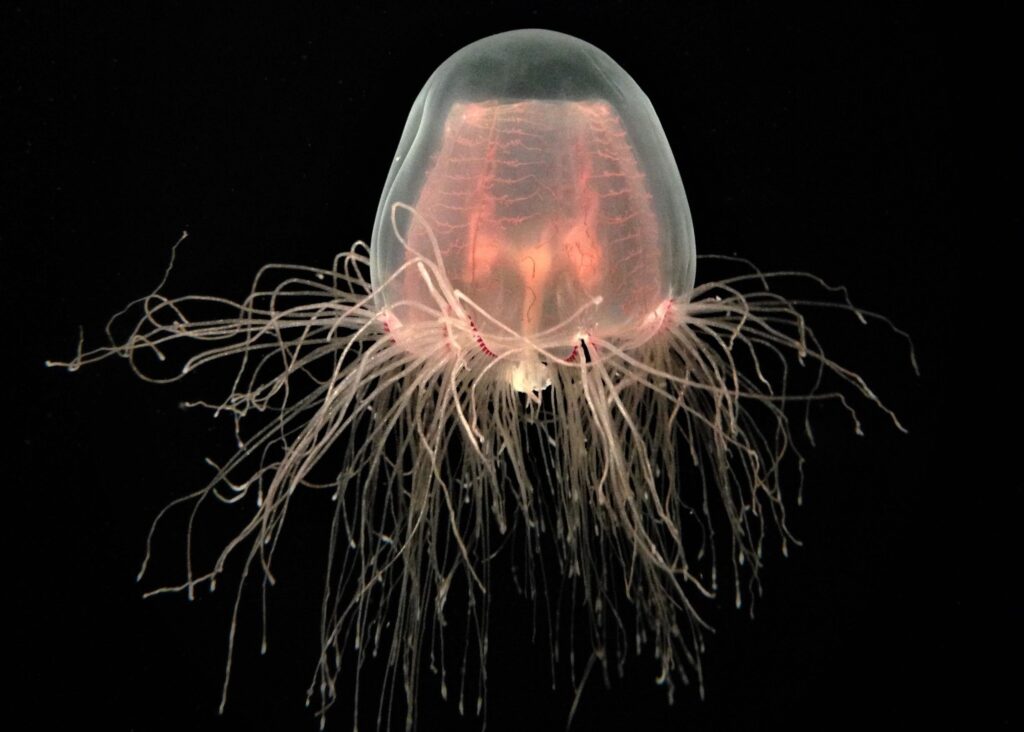

Humans have long hungered for the secret to eternal life on Earth — ancient practices like alchemy have made way for modern research on cellular rejuvenation and predictions of digital immortality. But for the species T. dohrnii, also known as the “immortal” jellyfish, turning back the clock on biology is just part of their genetic makeup. Now, to better understand the mechanisms behind the hydrozoan’s seemingly miraculous ability, a team of scientists at the University of Oviedo in Spain has successfully mapped the species’ genome.

Members of T. dohrnii start life as mere layers of cells and tissues, or polyps, attaching themselves to rocks or plants on the seafloor. After maturing into medusae, a state named for the marine animal’s resemblance to the mythical Greek goddess Medusa, the jellyfish become more vulnerable to hungry predators and environmental risk factors, like food scarcity. So, when deemed necessary, they return to their earlier polyp state to increase their chances of survival.

At that point, the creatures can clone themselves, creating a colony of polyps from one, all able to restart the cycle of maturity, with the ability both to sexually reproduce and asexually revert to polyps again. It’s unknown just how many times the T. dohrnii can perform this circular life process and whether it is an unlimited ability or not.

In an attempt to gain insight into this “biological immortality,” as the study authors refer to it, the team sequenced and compared the species’ genome to the genome of its closely related but non-“immortal” jellyfish relative, Turritopsis rubra.

The findings, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggest that T. dohrnii is better able to replicate and repair its DNA and maintain the ends of chromosomes, called telomeres — which, in humans, are found to shorten in length with age. The authors also identified gene variants associated with “stem cell population and intercellular communication.”

While helpful in understanding the mechanics of the jellyfish’s rejuvenation cycle, we shouldn’t assume we can directly relate the research to human aging, one of the lead authors, marine biologist Dr. Maria Pascual Torner, pointed out to the Wall Street Journal. “It’s a mistake to think we will have immortality like this jellyfish, because we are not jellyfish,” she said. Pascual Torner did indicate, however, that it may be possible to apply the knowledge her team unlocked to the general pathologies of aging.

Monty Graham, director of the Florida Institute of Oceanography and a jellyfish expert who was not involved in the study, agrees. “We can’t look at it as, hey, we are going to harvest these jellyfish and turn it into a skin cream,” he told Reuters, and added: “It’s one of those papers that I do think will open up a door to a new line of study that’s worth pursuing.”