Go into any elementary school library in the United States, and you’ll likely spot the bright green and red cover of the The Very Hungry Caterpillar. Much like the titular caterpillar’s never-ending appetite, children’s love for Eric Carle’s 1969 picture book appears to be endless.

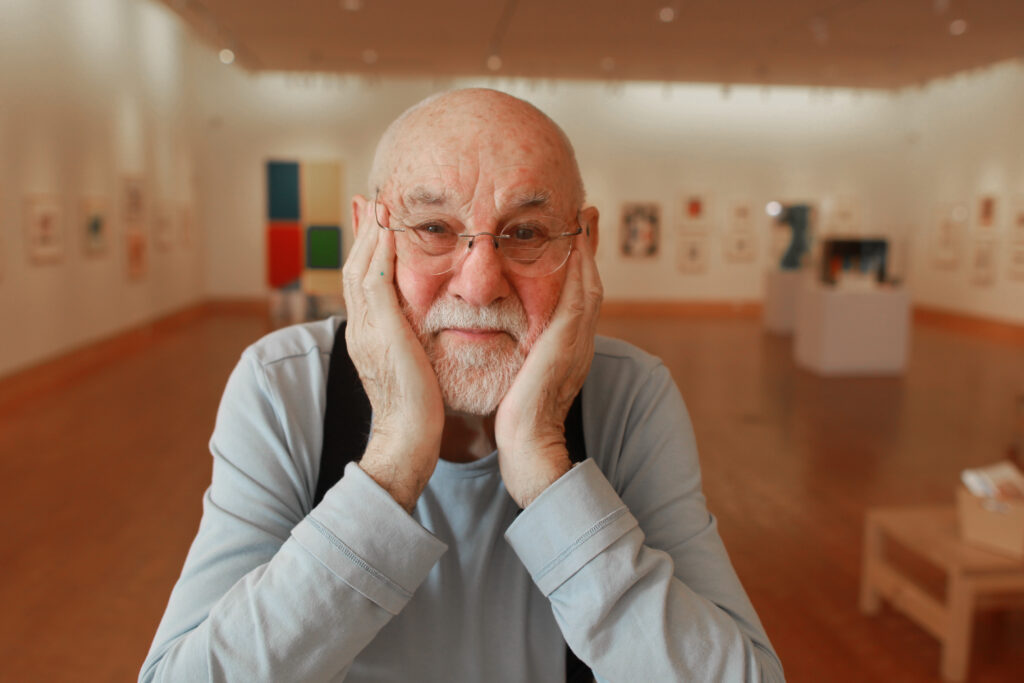

Though Carle wrote and illustrated more than 70 children’s books during his life, he is perhaps best remembered for this book (watch him read it in the video below), which encapsulates his signature colorful but simplistic design. It’s a children’s literary classic that sits alongside popular works from Judy Bloom and Dr. Seuss. But it also seems semi-autobiographical in some respects, inspired by the simple childhood walks he went on with his father and the hardships of a post-World War II Germany that would define his youth.

Early Years in a War-Ravaged Germany

Carle was born in Syracuse, New York, in 1929 to two German immigrants. His early days were relatively peaceful: Carle’s father would take him for nature walks, introducing him to the insect world and pointing out spiderwebs and bird nests. These moments would stick with Carle for the rest of his life and define so many of his books. As he told NPR in 2007, “I think it started with my father. He took me for long walks and explained things to me.”

Unfortunately, at the urging of his homesick mother, the family decided to return to Germany when Carle was 6 — “a decision they would deeply regret,” according to the Eric Carle Museum. Shortly after WWII began in 1939, Carle’s father was drafted and became a Russian prisoner-of-war. Back at home, young Carle experienced abuse from both Nazi soldiers and teachers and often went hungry.

“All of us regretted it,” he told NPR. “During the war, there were no colors. Everything was gray and brown and the cities were all camouflaged with grays and greens and brown greens and gray greens or brown greens, and … there was no color.”

However, the years spent in Germany also gave Carle his first preview into art. When he was 12 or 13, an art teacher secretly introduced him to Expressionism, per the Associated Press. In particular, Carle was moved by Franz Marc’s “Blue Horse” painting, whose colors and design later influenced his own work and inspired him to write The Artist Who Painted a Blue Horse.

Following the war, Carle studied art himself at Akademie der Bildenden Künste, an art school in Stuttgart. “Those four years were the most inspiring and exciting years of my artistic schooling,” he said, according to the Eric Carle Museum. He would gain the necessary knowledge to return to America at age 23 to pursue a career in art. With that, he left Germany behind.

From Advertising to Children’s Author

Though he would become known for his prolific catalog of children’s books, Carle didn’t establish himself as an author and illustrator until later in life. His early adulthood was marked by a journey in commercial artwork and advertising.

In 1952, Carle returned to New York with $40 and a dream. Using a fine portfolio he put together, Carle initially landed a job with The New York Times, working as a graphic designer in their promotion department. But “only five months after returning to America, Carle was drafted into the U.S. Army. Much to his chagrin, he was stationed in Germany because of his language skills,” per the Eric Carle Museum. “For two years he worked primarily as a mail clerk.”

By the following decade, Carle had returned to the Big Apple, where he spent years working in the advertising field, getting promoted to art director at an agency.

While Carle’s advertising work didn’t directly lead to a late career change to children’s author, it did open the door into that world. Bill Martin Jr., a children’s book author, was looking for an illustrator to bring to life his latest work when he noticed a red lobster Carle had designed for an ad.

Martin invited Carle to illustrate for his book, the popular 1967 Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See? That opportunity transformed Carle’s professional trajectory, shifting him from advertising director to picture book artist. He followed it up with 1,2,3 to the Zoo, the first book he wrote wholly by himself. However, it was his next book that would cement his place in children’s literature.

The basis for The Very Hungry Caterpillar, and much of his collaged artworks, sprouted from those long walks in nature with his father. “Through my books, I honor him,” Carle shared in a video while discussing his life’s work. While time spent outside would reveal the rich green, red, and other colors the author used for inspiration, the idea for his caterpillar was inspired by a hole punch. He imagined the holes in paper as rings of a bookworm, creating a first version of the book that was initially called A Week With Willi Worm.

Carle’s editor wasn’t keen on the ending, which featured a fat worm. After workshopping, the two eventually settled on a caterpillar, creating the iconic final image of a butterfly emerging from its cocoon. The book proved to be widely successful, selling 40 million copies in more than 60 languages.

“I think it is a book of hope,“ Carle said in a commemorative video celebrating 50 years of the book. “Children need hope. You, little insignificant caterpillar, can grow up into a beautiful butterfly and fly into the world with your talent. ‘Will I ever be able to do that?’ Yes, you will. I think that is the appeal of that book.”

Enduring Legacy

But Carle’s life was more than the success of just one book. Up until his death in 2021 at age 91, he encouraged children to imagine and explore the world around them through books like The Very Lonely Firefly (1995) and The Very Quiet Cricket (1990). Similar to the Bob Rosses and Fred Rogers of the world, Carle connected with children by teaching them on their level. Per Reading Rockets, the author received nearly 10,000 fan letters each year.

RELATED: I Love Books: The Social Impact Organization Striving to End Illiteracy in Kids — Exclusive

Carle was married twice and was the father of two children, Rolf and Cirsten, whose initials he often hid in his collages. In 2002, he and his late second wife, Barbara, opened the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in Amherst, Massachusetts, ensuring the works of many other illustrators can be appreciated for generations to come. “She was a force behind the museum. She was a force behind me,” Carle said of Barbara, who died in September 2015. Today, the museum has more than 8,500 illustrations that represent more than 200 artists, as well as an art studio, galleries, and a theater.

Though he may be gone, he left a lasting legacy in the field of children’s literature. Like a caterpillar becoming a butterfly, the life of his work doesn’t end, but rather is reborn through the joy of each new generation that reads it. To see more of Carle’s life in photos, including how he created his pictures using tissue papers, click here.