In Koasati, which is spoken in Louisiana and parts of Texas, the word “ihoochastontihchotok” means “bringing time back from the past to now.” It’s one of nearly 100 terms from an equal number of languages represented in author and photographer B.A. Van Sise’s latest book.

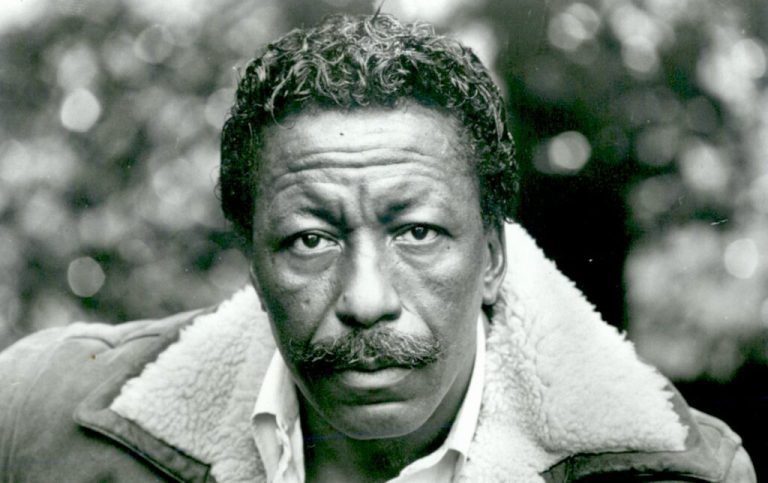

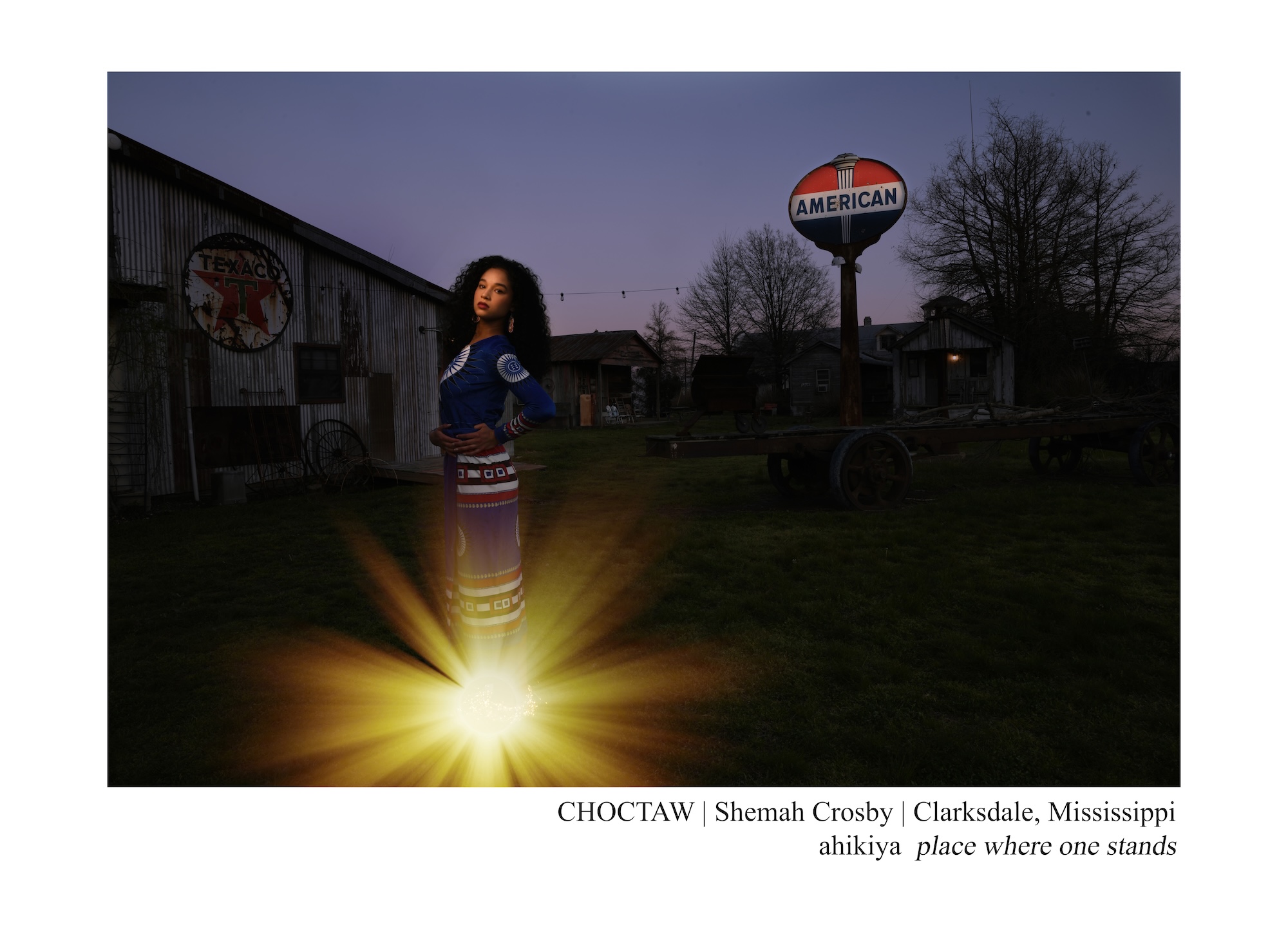

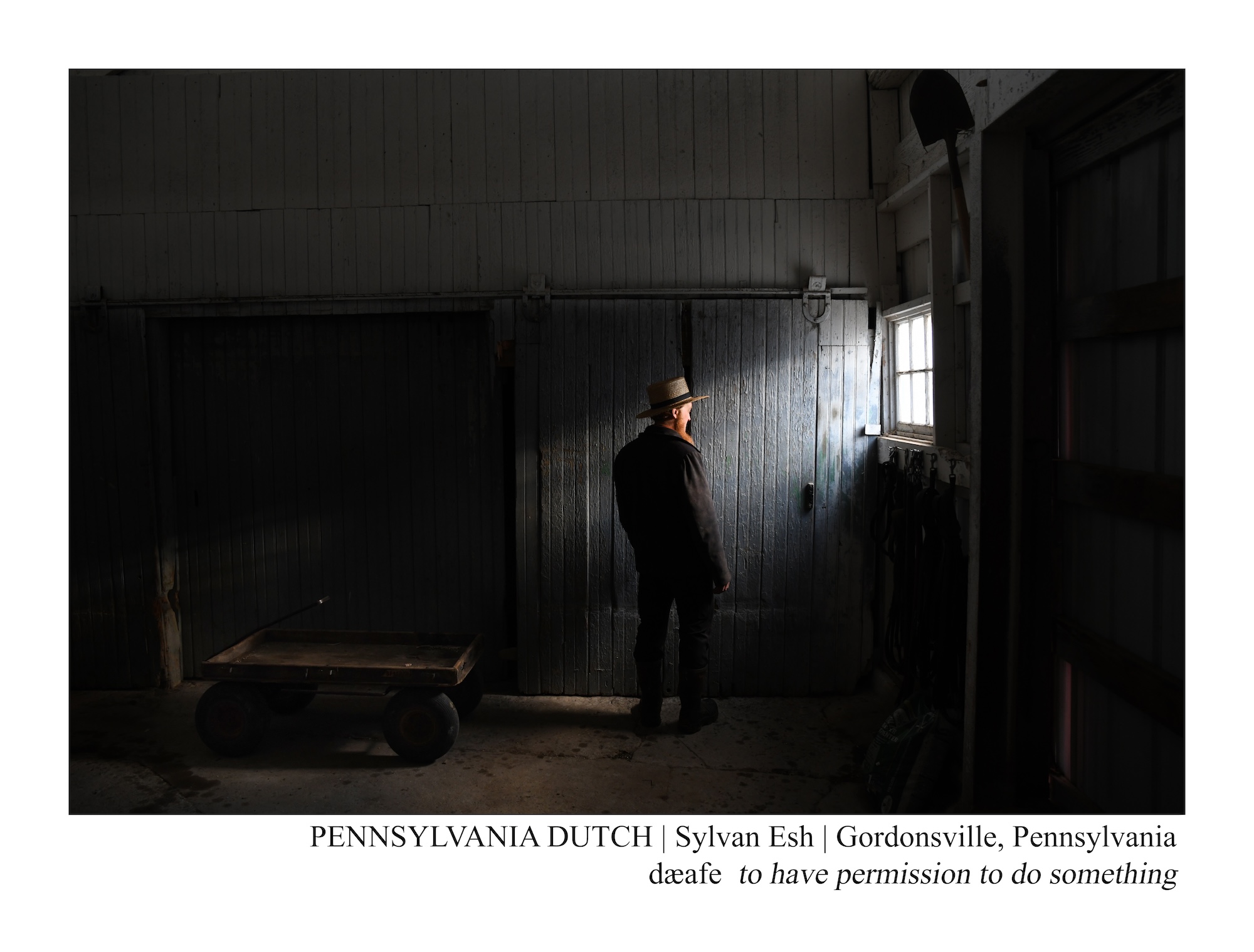

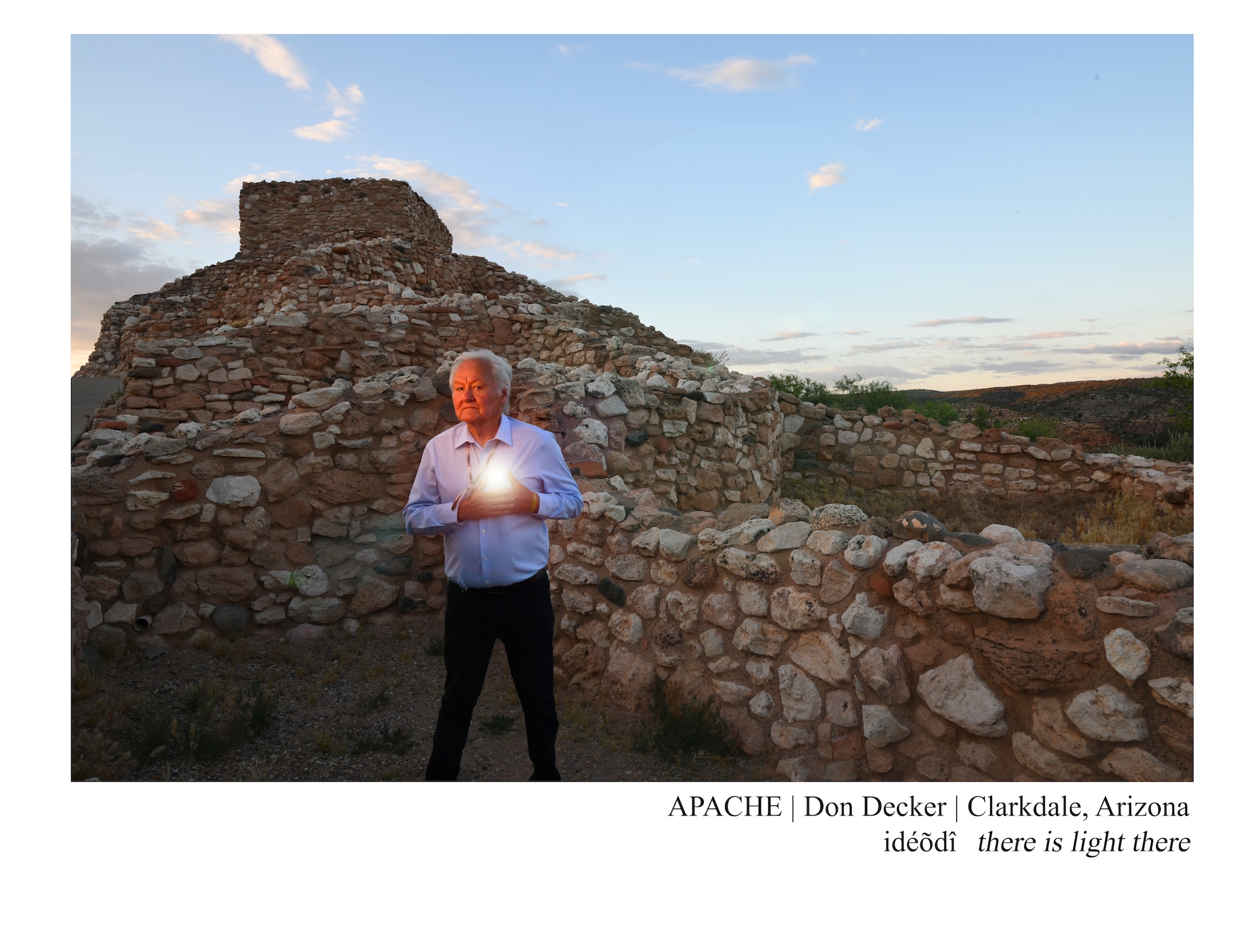

On the National Language, out Sept. 28, features evocative portraits of speakers and learners across the United States who are working to keep the country’s many endangered tongues alive, with each image encapsulating the meaning, history, and culture of the term that inspired it.

The project’s goal is to raise awareness for languages at risk of going extinct — from Navajo and Pennsylvania Dutch to Lousiana Creole and Judaeo-Spanish — and highlight the revitalization programs in place to prevent that.

“Language is a cultural binder. Every language has cultural concepts unique to them that exist only in their language; Italians have no word for ‘privacy’ but a word for ‘doing something beautiful and making it look effortless,’” Van Sise explained to Nice News. “In English you can ‘do something on a whim,’ ‘get the gist of an idea,’ or ‘run amok into a brouhaha’ and be absolutely unable to say any of that in any other language. Language is tied to who we are.”

The photos are accompanied by information on the languages and their revitalization efforts, with select poetry and essays written by their speakers interspersed as well. Over the span of three years, Van Sise traveled to 48 states to meet with and learn from the people he photographed, collaborating with them on the concepts for their portraits.

“We’ve got so many incredible people — especially young folks — in so many communities who are just fighting like hell to not only safeguard these traditions but build a bridge to a brighter future,” he said. “And having met and now knowing so many, I’m pretty bullish on their chances.”

One of those individuals is Amber Hayward, director of the Puyallup Tribal Language Program. The program works to revitalize Twulshootseed, spoken by tribes living around the Puget Sound area in Washington state.

“America is a monolingual country. Most countries of the world are bilingual and even multilingual. When we speak more than one language, we connect to those ancestors who spoke that language, we get insights into their world,” Hayward explained. “We see the world through their eyes, and can better connect to our cultural practices, ceremonies, and beliefs. When language is lost, our people are lost. When we speak our language, we give our ancestral ways life again.”

Joshua D. Hinson, who also goes by the name Lokosh and is the executive officer of the Chickasaw Nation Language Preservation Division, added: “Our language is what sets us apart from all other people on the planet. It carries millennia of ancestral worldview and spiritual power. We will not cease to exist as a people nor as a sovereign Native nation if our language goes to sleep, but we would be all the poorer for it.”

For Van Sise, getting to experience the languages firsthand was the apex of his journey documenting their speakers. “My absolute favorite thing was the absolute riot of language that was happening around me,” he shared. “I went to so many shoots where there were families along and everybody was yakking away in their languages around me.”

Forty-six of the images are set to go on display at Los Angeles’ Skirball Cultural Center from Oct. 17- March 2, and the exhibit’s curators had the idea to go back to some of the locations and get audio of the book’s collaborators conversing.

“The folks who visit [the exhibition] get to actually hear and live inside the sound of the language and get a bit of the treat that I did,” said Van Sise. “It’s great. It’s poetry in motion.”

RELATED: “Six Times the Size of Yosemite”: The Proposed Marine Sanctuary off California Coast