The deep, vibrant blue you often see in ancient Egyptian depictions of royalty is no ordinary color — made from calcium copper silicate, it may be able to enhance energy efficiency, boost solar electricity, and help create counterfeit-proof ink. Originally used around 5,000 years ago, it’s considered the world’s oldest synthetic pigment.

Its usage faded by the Renaissance period, and eventually, the recipe for how to make Egyptian blue was lost. But thanks to its potential applications in modern times, there’s recently been a renewed interest in the pigment, and a Washington State University-led research team has now devised 12 recipes to re-create it.

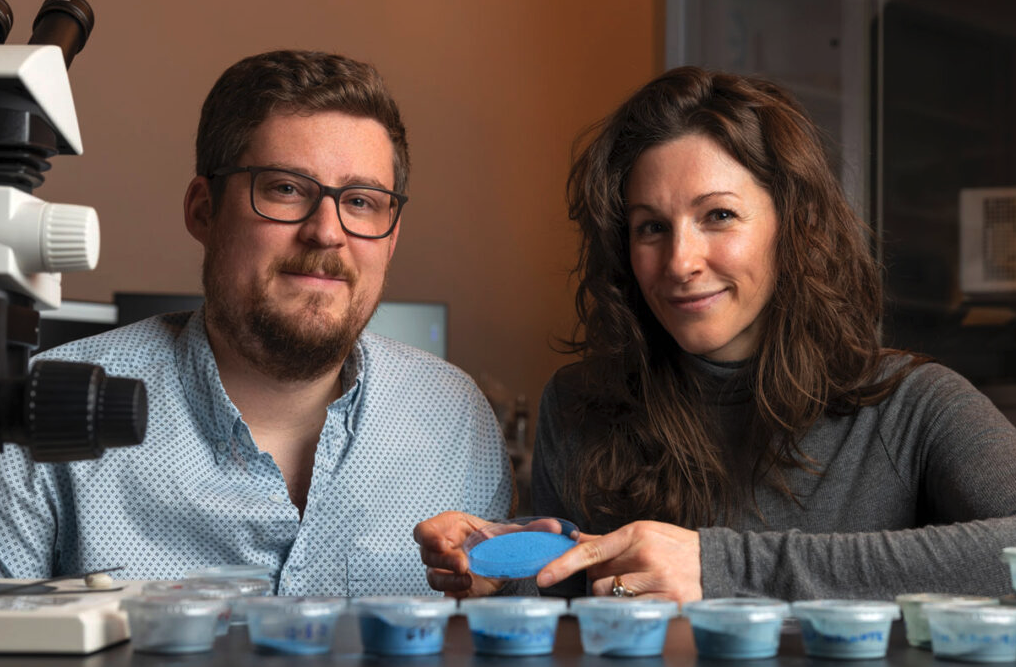

“It started out just as something that was fun to do because they asked us to produce some materials to put on display at the museum, but there’s a lot of interest in the material,” John McCloy, first author of a study detailing the process, said in a press release.

Publishing their findings in NPJ Heritage Science, the researchers used silicon dioxide, copper, calcium, and sodium carbonate to create various formulas of the pigment. To mimic the firing temperatures that would have been available to ancient Egyptians, they heated the ingredients to 1,832 degrees Fahrenheit for up to 11 hours. Once the mixtures had cooled, the scientists used novel techniques to compare them to the blue in ancient Egyptian objects.

In the study, the team noted that Egyptian blue isn’t one specific shade — it’s a diverse array of blue hues. Back in ancient Egypt and Rome, the pigment offered a more affordable and versatile alternative to blue stones like turquoise and lapis-lazuli. The researchers explained that it may have traveled through formal trade routes, and was likely produced at different locations from where it was used.

“You had some people who were making the pigment and then transporting it, and then the final use was somewhere else,” McCloy said. “One of the things that we saw was that with just small differences in the process, you got very different results.”

The team also discovered that a little calcium copper silicate, or cuprorivaite, goes a long way. Just 50% of cuprorivaite resulted in a deep blue shade, and “it doesn’t matter what the rest of it is,” McCloy said. “Every single pigment particle has a bunch of stuff in it — it’s not uniform by any means.”

These new recipes could open doors for its uses today. In 2018, a study found that surfaces coated in the fluorescent pigment can give off nearly 100% as many photons as they absorb, meaning the hue could help reflect the sun and thus cool rooftops and facades. Another study demonstrated that windows tinted with Egyptian blue may be able to convert fluoresced energy to electricity.

And thanks to the light the color emits, which is close to the infrared section of the electromagnetic spectrum and invisible to the human eye, it could help create security ink. But for now, the Egyptian blue samples are on display at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, where they’ll become a permanent part of a new gallery centered on ancient Egypt.

“We hope this will be a good case study in what science can bring to the study of our human past,” McCloy said. “The work is meant to highlight how modern science reveals hidden stories in ancient Egyptian objects.”

RELATED: Chemical Imaging Reveals “Hidden Mysteries” of 3,000-Year-Old Egyptian Tomb Paintings