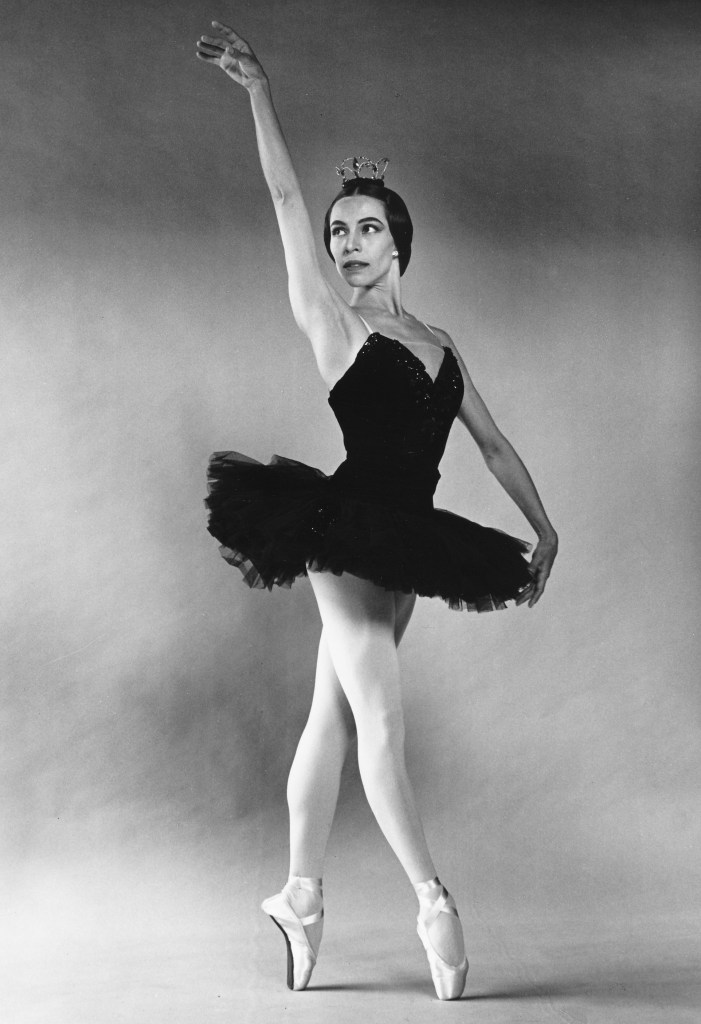

It’s impossible to tell the story of American ballet without giving credit to trailblazer Maria Tallchief, who would’ve celebrated her 100th birthday earlier this year. The legendary dancer leapt and twirled her way to international stardom during the mid-20th century and is widely considered America’s first prima ballerina.

“A ballerina takes steps given to her and makes them her own,” Tallchief once said — and those ambitious steps eventually propelled her from the American South to gilded stages around the world.

Tallchief was born in 1925 as Elizabeth Marie Tall Chief in Fairfax, Oklahoma, to an affluent Osage family during a period when dozens of members of the Indigenous tribe were murdered by those seeking to acquire their oil rights. She grew up learning the traditional ways of her people from her grandmother Eliza. The family matriarch gave her an Osage name, Wa-Xthe-Thonba, which means “Two Standards” and reflects a life dancing to both traditional Native songs and the greatest works of classical ballet.

The soon-to-be prodigy’s Scottish-Irish mother, who grew up poor, sent her to piano lessons and envisioned her a concert pianist, but young Tallchief and her sister, Marjorie, both took a liking to ballet soon after being introduced to the expressive art form.

“Through their artistic skill and discipline, these Osage sisters would become famous in the 20th century not as victims of colonial violence but as leading forces in the world of ballet and global culture,” David Helvarg wrote for American Indian Magazine in 2023.

The family moved in 1933 to Los Angeles, where Tallchief eventually studied under Bronislava Nijinska, famous choreographer and former dancer with the Ballet Russes, one of the most influential ballet companies of the 20th century. At 17, Tallchief moved to New York to be an apprentice for the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo.

Tallchief and her daughter, Elise Paschen

Tallchief stood strong in her American — and Osage — heritage. Many dancers of the time adopted Russian-styled stage names, and Ballet Russe encouraged her to change her last name to the more Slavic-sounding “Tallchieva,” per the Oklahoma Historical Society. Tallchief refused, instead deciding to remove the space from the two-word last name she was born with.

She soon took the role of soloist with the Ballet Russe, and after touring for several years, Tallchief met the famed Russian choreographer George Balanchine when he joined the company in 1944. The two fell in love, and Tallchief became Balanchine’s wife and muse, inspiring many of his works during the 1940s.

In 1947, Tallchief became the first American to dance with the Paris Opera Ballet to the delight of French audiences, who were especially intrigued by her Native American background. Tallchief and Balanchine returned to New York City shortly after to join the Ballet Society, which later became the New York City Ballet. Her time there as prima ballerina — the principal female dancer — put both her and the company on the marquee map.

Two years into her lengthy run with the New York City Ballet, Tallchief originated the title role in Balanchine’s retooling of Firebird, a notorious avant-garde piece scored by Igor Stravinsky. She recalled being terrified of the tremendous but technically demanding opportunity.

Tallchief performing in Firebird

“When I first danced Firebird, [it] was the most frightening and challenging thing of my life, and everybody in New York City was waiting to see what was going to happen because I had not danced such an important role,” Tallchief later said in an interview.

But audiences and critics raved about Tallchief’s ability to combine energy and passion with technical prowess in her dancing, and Firebird became one of her signature roles.

In 1954, Balanchine premiered his own restaged version of The Nutcracker at City Center with Tallchief as the Sugar Plum Fairy. Her enchanting performance, along with Balanchine’s choreography, helped skyrocket The Nutcracker into a holiday-season sensation that the New York City Ballet still performs to this day.

“Does [Tallchief] have any equals anywhere, inside or outside of fairyland?” wrote critic Walter Terry of her illustrious performance in the production’s opening. “While watching her in The Nutcracker, one is tempted to doubt it.”

Six years later, Tallchief became the first American to dance at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow. And in 1962, she performed in “An American Pageant of the Arts,” a televised event that promoted fundraising for what would later become the Kennedy Center. Tallchief herself later received a Kennedy Center Honor in 1996 for her innumerable contributions to the world of ballet.

Though Balanchine and Tallchief eventually divorced, they continued to work together at the fledgling New York City Ballet. Tallchief married twice more and had one child, Elise Paschen, with her third husband. Paschen went on to write a poem that inspired the book Killers of the Flower Moon, eventually made into a movie, which details the Osage murders of the 1920s.

After retiring in 1965, Tallchief devoted her life to directing, choreographing, and teaching. She established the Chicago City Ballet with her sister, Marjorie, who’d also made a name for herself as a ballerina in Europe and had become the first American and Native American to be named a “star dancer” for the Paris Opera Ballet in 1957. Tallchief died in April 2013 at age 88, leaving behind a legacy of groundbreaking artistry and inspiration.

Tallchief in 2006

Despite having dropped piano for ballet as a child, Tallchief always maintained an admiration for the music that laid the foundation of her dance career. Per Time, in dancer Allegra Kent’s autobiography, Once a Dancer, Kent marveled at how precisely Tallchief molded her movements to the melodies on stage, matching their moods and intensities while leaving nothing lost to translation.

“From your very first plié, you are learning to become an artist. In every sense of the word, you are poetry in motion,” Tallchief once said. “And if you are fortunate enough … you are actually the music.”