Winter’s harsh weather conditions famously send certain animals, like black and grizzly bears, running for the hills — and into their dens, more specifically, where their renowned ability to sleep for months on end helps them avoid the cold altogether. But during the most frigid months of the year, other animals are actually living their best lives. (If you consider yourself among that group, you’re part of the chionophile club.)

With winter on the horizon, we’ve rounded up seven animals with a penchant for the chilly season. Some of the species on this list likely won’t come as a surprise, but others may be lesser-known to you, including a fascinating microscopic invertebrate that’s been around for millions of years.

Polar Bears

It could be argued that the polar bear is winter’s unofficial mascot, with public interest and familiarity undoubtedly buoyed by Coca-Cola, which has featured the white winter giant in its advertising since 1922. The company clearly saw an opportunity to create an association in consumers’ minds with the bears and its own beverage as two things that do best when they’re icy cold.

Polar bears are among the largest bears in the world (tying with kodiaks), and those thick white coats are quite oily — making it difficult for excess water to penetrate their fur and chill them. While seals are their food of choice, the bears have also been known to make a meal of walruses, beluga whales, birds, and carrion.

Being so attuned to the cold, their main activities — beyond the over 50% of time spent hunting — include resting, mating, and occasionally playing, and are largely carried out on ice sheets.

Emperor Penguins

The world fell in love with the emperor penguin when the 2005 documentary March of the Penguins brought to light the extraordinary measures these determined creatures take to mate and raise their young in the frigid Antarctic climate. With feathercoats that keep them warm in the freezing cold, they establish their colonies on plates of ice.

Emperors are the largest of the penguin species, with adults boasting a wingspan of approximately 32 inches. They’re incredibly skilled swimmers capable of traversing over 2,500 miles at sea in search of food, and have been recorded diving for more than 25 minutes at a time — reaching a depth of 1,640 feet, the deepest known dives made by any bird, per the Antarctic and Southern Coalition.

Caribou

Caribou and reindeer are actually the same species, Rangifer tarandus. In Europe and Asia, “reindeer” refers to domesticated and semi-domesticated animals, whereas caribou is used for the wild ones populating North America.

One reason that caribou prefer the cold is that they’re a target for bugs in warmer weather. (Humans who are regularly targeted by summertime mosquitos can surely empathize.)

Fun fact about caribou: Both males and females grow antlers!

Japanese Macaques

Appropriately nicknamed “snow monkeys,” Japanese macaques are unquestionably one of the more entertaining species on this list — what’s not to love about an animal that likes to make snowballs, plays leapfrog, and enjoys a stress-reducing soak in Mother Nature’s hot tub on the regular?

Japan’s Jigokudani Monkey Park was established in 1964 as a refuge for the macaques, which had previously been hunted after the development of nearby ski resorts forced the animals into towns, according to CNN. But now their home within Joshinetsu Kogen National Park means the primates have a hot spring of their very own, appearing largely oblivious to the tourists who flock to enjoy their antics.

And while the animals are not biologically equipped to engage in a full-fledged snowball fight, that doesn’t mean they hold back on partaking in some cold weather mischief. “I’ve observed many juveniles trying to steal each other’s snowballs,” Rafaela Sayuri Takeshita, a PhD student at Kyoto University’s Primate Research Institute, told National Geographic.

Arctic Foxes

Touted by Nat Geo as “an incredibly hardy” cold weather animal, the small Arctic fox — which weighs between 6 and 10 pounds in adulthood — will simply burrow into the snow to escape a blizzard. Their white or occasionally blue-gray coats are, like many of their cold weather compatriots, changeable based upon the season.

While their white winter coats make for excellent camouflage from predators, in warmer weather their fur becomes brown or gray, all the better to disguise them among summer tundra plants and rocks.

During winter, when prey is scarce, these clever creatures will trail polar bears while they hunt and subsist upon the leftovers.

Winter Weasels

A winter weasel’s slim form allows it to squeeze into tight places where its prey — like mice and chipmunks — can be found, but its small, sleek shape simultaneously puts the animal at somewhat of a disadvantage, as described in Northern Woodlands magazine. Weasels, also called ermines, lose their body heat more quickly than chubbier animals, so to adapt, they possess a high metabolic rate, which means they’re more or less constantly moving — and, of course, eating.

The animal’s coat turns from light brown to white in preparation for winter, a change that takes its cue from shortened daylight hours during colder months. This white fur serves as an essential camouflage from predators in the snow.

“They are well-adapted to snowy environments and range into alpine areas. They have been documented year-round living at 2,000-3,000 feet in the Sierra Nevada, California, and commonly live in tundra habitats throughout northern Canada and Alaska,” per the Alaska Wildlife Alliance.

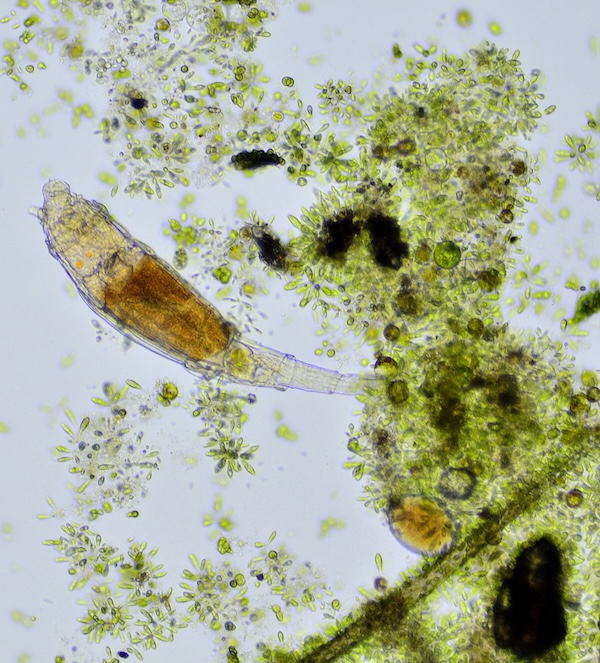

Bdelloid Rotifers

Although it’s the smallest animal on the list, the bdelloid rotifer has proven to be the most resilient of all winter-loving species. In a 2021 study, the microscopic, multicellular organism was found to be alive after spending 24,000 years in a frozen state.

“It’s hard for most of us to imagine an animal staying alive for 24,000 years,” said Doug Levey, a program director in the U.S. National Science Foundation’s Division of Environmental Biology. “This study shows that life exists practically everywhere on Earth, and that exciting discoveries about it are boundless.”

Stas Malavin, of Russia’s Institute of Physicochemical and Biological Problems in Soil Science, told the Press Association: “The takeaway is that a multicellular organism can be frozen and stored as such for thousands of years and then return back to life — a dream of many fiction writers.”

Perhaps even more remarkable: The species is female-only and is believed to have been reproducing asexually for roughly 40 million years, per Nat Geo.