Certain people just seem to embody wisdom: grandparents and teachers, the changemakers we admire from afar, the intellectuals whose ideas have influenced our own. However, given that cultures vary widely throughout the globe, it would make sense that the criteria for being deemed “wise” would as well.

To test that hypothesis, researchers from the University of Waterloo in Ontario enlisted 2,650 participants on five continents to analyze their perceptions of wisdom. Interestingly, across all locations, people agreed that thinking logically and reflectively and taking others’ thoughts and feelings into consideration are what makes a person wise.

“Understanding perceptions of wisdom around the world has implications for leadership, education, and cross-cultural communication,” Maksim Rudnev, a postdoctoral research associate in psychology at Waterloo and the study’s lead author, said in a news release. “It is the first step in understanding universal principles in how others perceive wisdom people in different contexts.”

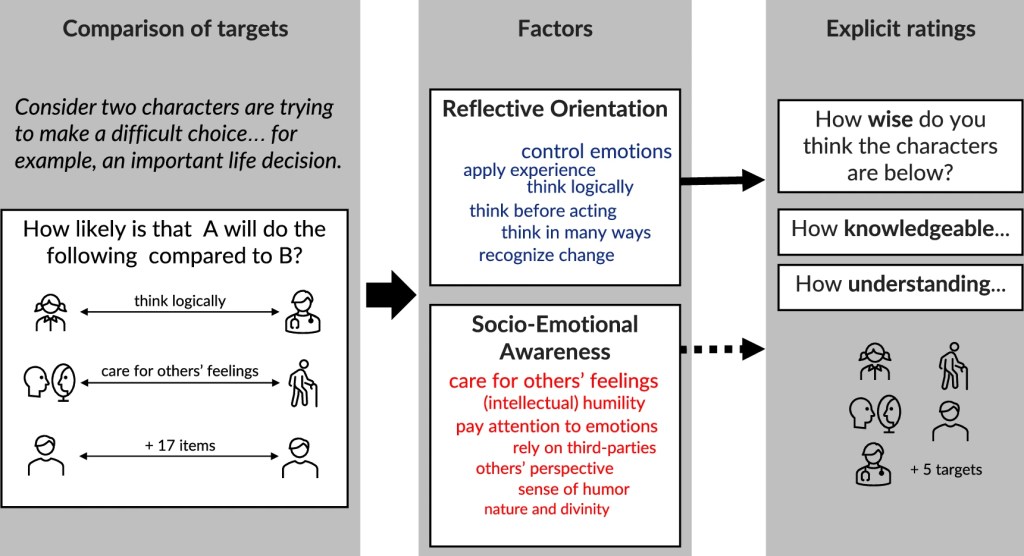

The team arrived at their findings, published in the journal Nature Communications, by giving participants descriptions of 10 specific individuals, including “doctor,” “politician,” and “religious person,” and asking them to compare pairs of these people based on 19 characteristics previously identified as being associated with wisdom.

Then, enrollees explicitly rated how wise they thought a person was as well as how much of each characteristic they possessed.

Study participants lived in Canada, China, Ecuador, India, Japan, Morocco, Peru, Slovakia, South Africa, South Korea, and the United States. Their converging perceptions of wisdom represented two dimensions: reflective orientation ( i.e. thinking logically, emotional control, thinking in many ways, etc.) and socio-emotional awareness (i.e. sense of humor, awareness of bodily expressions, and intellectual humility, etc.).

“To our surprise, the two dimensions emerged across all cultural regions we studied, and both were associated with explicit attribution of wisdom,” Rudnev said.

“While both dimensions of wisdom work together, people associate wisdom more with the reflective orientation. If someone is viewed as not able to reflect and think logically, then perceptions of them as socio-emotionally competent and moral won’t compensate,” senior corresponding author Igor Grossmann added.

Another insight from the research is how participants viewed themselves, one of the 10 targets they were asked to rate.

“Interestingly, our participants considered themselves inferior to most exemplars of wisdom in regard to reflective orientation but were less self-conscious when it comes to socio-emotional characteristics,” Rudnev explained.

Researchers specifically sought to analyze cross-cultural perceptions of wisdom while filling a gap in existing research. Most of the prior scholarship on social judgment has come out of Europe and North America, “with a dearth of research on social judgment in the Global South,” per the paper.

The team also identified a future area of study that may hold insight. “A particularly intriguing question for future research is whether people are more likely to trust individuals demonstrating unique features of wisdom in different contexts,” the authors wrote.

For example, they could explore whether people are more willing to trust those they rate high in reflective orientation when it comes to complex problem-solving scenarios, while turning to socio-emotional awareness stand-outs for things like offering solace in times of grief.

They added: “Investigating these relationships will deepen our understanding of wisdom’s nuances and its diverse interpretations across cultures.”