Many artists dream of one day having their work displayed in prestigious galleries around the world for the masses to admire. For Oliver Jeffers, though, there’s a unique reverence to inviting only a small group of people to bear witness to his artistic process and portraits.

In November 2014, the Northern Irish visual artist began The Dipped Painting Project — a series of performances during which he dipped his own fully painted portraits halfway into vats of colored enamel paints, permanently hiding portions of the images in the process. Prior to the paintings being dipped, he intentionally didn’t memorialize them with photographs. Instead, he wanted those present at the time of the dippings to be the only witnesses to the portraits in their unobstructed states.

“It’s an inspection of what we consider beautiful. Just because you cannot see it anymore, doesn’t mean it’s not there,” he told Nice News of why he paints the portraits in their entirety. “Knowing that there will be no existence of the complete portrait afterwards forces people to look at it in a different way, which is a little bit of an analogy for life in a very concentrated amount of time.”

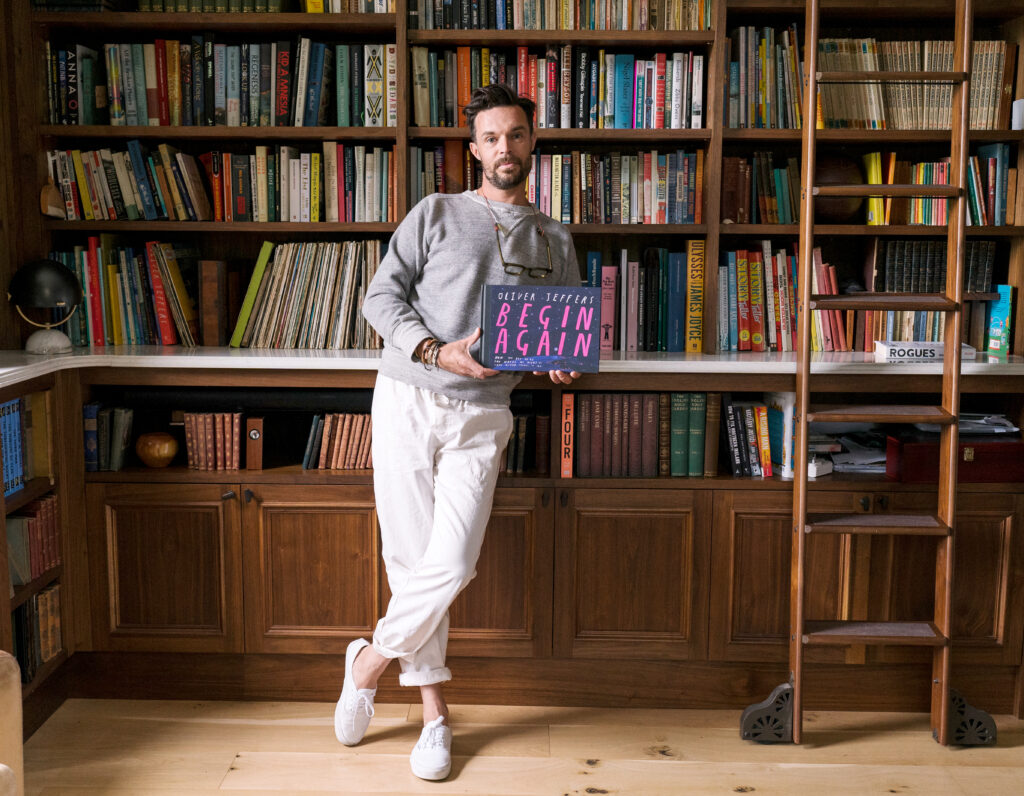

In addition to creating unique portraits, 46-year-old Jeffers is an award-winning author and illustrator of over 20 books, primarily for children, but the stories are filled with wisdom and moving messages that apply to everyone. His previous books include How to Catch a Star, Lost and Found, and Up and Down — and his much-anticipated latest book, Begin Again: How We Got Here and Where We Might Go — Our Human Story. So Far., hit bookstands Oct. 3.

Begin Again, Jeffers’ first illustrated book specifically for readers of all ages, opens with a simple yet complex question: “Where did we begin?” He then goes on to explore humanity’s past, present, and hopes for the future, filling pages with deeply thoughtful language against a backdrop of vibrant colors and illustrations of stars, planets, hands, feet, and flowers.

It’s both special and rare to come across a story as profound as it is accessible, and one that doesn’t gloss over death or struggle yet still exudes optimism and a sense of peace. There are messages about learning from the past while moving forward and the power of lifting each other up in a world that often feels like it’s telling us to put one another down. Each page is a kind invitation to ponder unanswerable questions and make space for moments of awe in this universe we live in — and the body and mind we experience this life with.

How does he manage to bridge the space between uncertainty and hope? What advice does he have for those who struggle to maintain an optimistic perspective? And how has fatherhood influenced his work? Nice News interviewed Jeffers to find out and learn more about his new book and thoughts on progress, mortality, and, as he put it, “the sheer joy of being alive in the first place.”

What is the significance of the name Begin Again? Did you know that was going to be the title all along or did it come later in the process?

It came pretty early on and I kept wondering if there was a better title. I couldn’t come up with anything else because it just seemed simple, optimistic, and easy. It is easy to access, and it’s worked on a number of different levels. It works in geographic terms, it works in terms of the drawing board, and it’s like a re-evaluation of our purpose.

Do you have any advice for those who struggle to feel a sense of optimism?

We easily forget how far we actually have come. Of course, so much inequality still exists, and at times, it feels like we’re sliding backwards. But if we go back to our grandparents’ generation, many aspects of life are better than it was 100 years ago, and I’m optimistic that things will continue to get better.

There are more solutions for things than we’re even aware of, but there needs to be unity. We need to recognize how much work there is to be done. There’s been a bit of reckoning over the last couple of years where we’ve started to recognize that the old rules that used to work for some aren’t working for all, and that things need to change. But just the fact that we’re recognizing that at all is a step in the right direction.

You mention “play” and “laughter” in Begin Again. Do you think adults lack both of those things as we get older? If so, why does that matter and how do you cultivate them in your life?

I do think we lose them, but come back to play and laughter in a lot of ways. I often say that all children are born artists. We just forget how to do that as we grow up because of self consciousness, or this idea of saving face, or you don’t want to look silly. But I think people should investigate whose validation it is that they’re actually seeking. What is it that they really care about? There’s a lot more room for joy and curiosity in our unwritten future.

Your book and other projects, like The Dipped Painting Project, explore mortality and being alive. In your eyes, how can reflection on life, death, and renewal help us as a collective?

I think it’s the idea of those who lose themselves to this existential battle with the intricacies of life that ultimately don’t matter. When they consider the brief flash of a firework that life is, and the sheer chances of existing, the question is this: As the Mary Oliver quote says at the start of Begin Again, is this what I want to do with my “one wild and precious life”?

There’s a tendency to focus on being right, because it proves the past, but it can also drag you down. I try to focus on the things that are important about how I want to feel as a human being and how my actions can lead to a better, although unknown, future.

Can you tell us a bit more about The Dipped Painting Project? And did this project influence Begin Again at all?

I sort of fell into The Dipped Painting Project accidentally by trying to look at the world scientifically and emotionally at the same time, and ended up making work that I was hiding. The Dipped Painting Project ultimately came about as a result of that, and was loss, and memory, how memory forms identity, the malleability of memory actually, and how we alter stories to suit what we need from them. It was really about the impermanence of it all.

One common thread with The Dipped Painting Project and Begin Again is the idea of a lack of permanence. Mortality and the sheer joy of being alive in the first place.

You share two children, Harland and Mari, with your wife, Suzanne. Being a dad of two, how has the experience of fatherhood carried over into your work?

It’s been quite interesting because it sort of started this whole influx of people asking if the type of books that I make would change after becoming a parent. I think they were thinking like, “Oh, are you going to write pirate books if your kids are [into] pirates?” but it really led to this kind of dawning realization or epiphany that was like, “Hold on a second — when my son was born, when my daughter was born, they arrive as totally raw balls of clay, they know nothing, and they will have to be taught everything. They will have to be told all of these stories that make sense in their world.” That was wildly intimidating. But then I realized they don’t know any of the stories of what’s happened in the world. They can be told better stories than the ones that have broken us.

On a practical level, I definitely had to change the way that I work. I used to be able to work through the waves of momentum when they hit, but now I have to be more structured about my time. And tolerate a lot of interruptions.

Have you noticed any changes in yourself or the way you look at the world from creating Begin Again?

I feel I’ve got a sense of urgency to everything that I do and a renewed way. And I see a beautiful, simple truth about life that I just need to share.

Begin Again is out now.

RELATED: Inside the Life of Eric Carle, “The Very Hungry Caterpillar” Author Who Got a Late Career Start