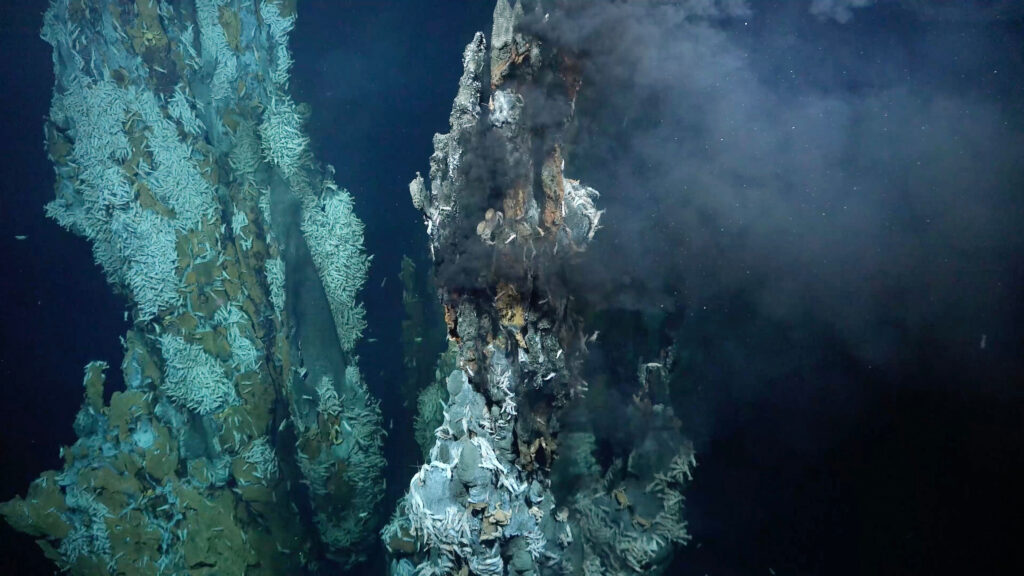

During a recent oceanic expedition, a team of international scientists found three previously undiscovered hydrothermal vent fields in the Mid-Atlantic Ridge via the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s new research vessel, Falkor (too). Per a press release from NOAA Ocean Exploration, this scientific expedition was the first since the 1980s to find vent fields in the ridge location, which stretches more than 400 miles.

Hydrothermal vents are known as “openings on the ocean floor from which heated, mineral-rich water emerges,” per NOAA. Here, animals (like the bigfin squid, seen below) can survive and rich ecosystems can flourish — even with the absence of sunlight.

Finding the three black smoker vent fields “was thrilling and history-making in itself,” NOAA said in the release.

According to Mongabay, this chimney-like effect is the result of “iron sulfide deposits that gushed out dark, sulfurous plumes with temperatures up,” noting temperatures as high as 644 degrees Fahrenheit that are hot enough to melt lead. Still, the vents are active with species that are suited to survive (and thrive) even in this intense setting.

The expedition proved its importance for various reasons, including gathering “essential” information about hydrothermal systems; providing data about the animal communities living at the vents; providing “new geological/geochemical data on oceanic core complexes, furthering our knowledge about these geological features”; and demonstrating how to accelerate research into these underwater systems.

To find these vents, which are notoriously difficult to access, scientists specifically targeted areas where “mantle rocks are exposed to seawater (oceanic core complexes), and where the chemical reaction between these rocks and seawater, known as serpentinization, can result in hydrothermal activity.”

Ultimately, they were able to discover the hydrothermal vents, one at about 6,500 feet below the surface, using “cutting edge technologies.”

The team used a multibeam sonar system to map the seafloor and autonomous underwater vehicles to collect physical ocean data. Additionally, they used a remotely operated vehicle named SuBastian to explore ”sites of interest.”

With the strategic use of these innovative technologies, the team has shown that Falkor (too) is an effective and “powerful” tool for exploring the deep sea.

Now, researchers are using this information to continue investigating more about the area, and also to help better understand “the potential impacts of deep-sea mining of hydrothermal metal sulfide deposits for regional planning purposes.”

It’s been reported that deep-sea mining on hydrothermal vents can threaten biodiversity and spread toxic heavy metals in the pursuit for minerals, such as cobalt and nickel.

However, Dawn Wright, a deep-sea biologist who was not on the expedition, told Mongabay in an email, “The discovery, not only of additional active venting sites, but the shocking abundance of life at these sites, should now, thankfully, exclude these sites from consideration for mining.” She added: “There is still so very, very much more that we need to learn about how these ecosystems function, how nutrients are cycled among and within the vent animals, and the sheer biodiversity of these animals.”

One thing’s for sure: With more than 80% of the underwater realm still “unmapped, unobserved, and unexplored”, there’s no shortage of opportunities for exploration. As technology becomes more powerful and more refined, it’s exciting to wonder what will be revealed next.

RELATED: Award-Winning Photographer Laurent Ballesta Showcases Diverse Sea Life Under Antarctic Ice: Photos