For the past five years, British artist Justin Bateman has been creating intricate portraits out of pebbles and stones. His work is striking in its level of detail and scale, with pieces ranging in size from 10 square feet to over 80. And aside from a few permanent commissions, they’re all ephemeral — arranged on beaches and forest clearings. It wasn’t a medium he set out to master, but it’s since become something of a calling: To date, he’s made 120 works of art using over 1 million stones.

“I had no intention to make this many, but as soon as I decide to take a break, a new one starts to play on my mind,” Bateman, 47, wrote in a statement shared with Nice News. He added, “The world is a collection of masterpieces, waiting to be assembled.”

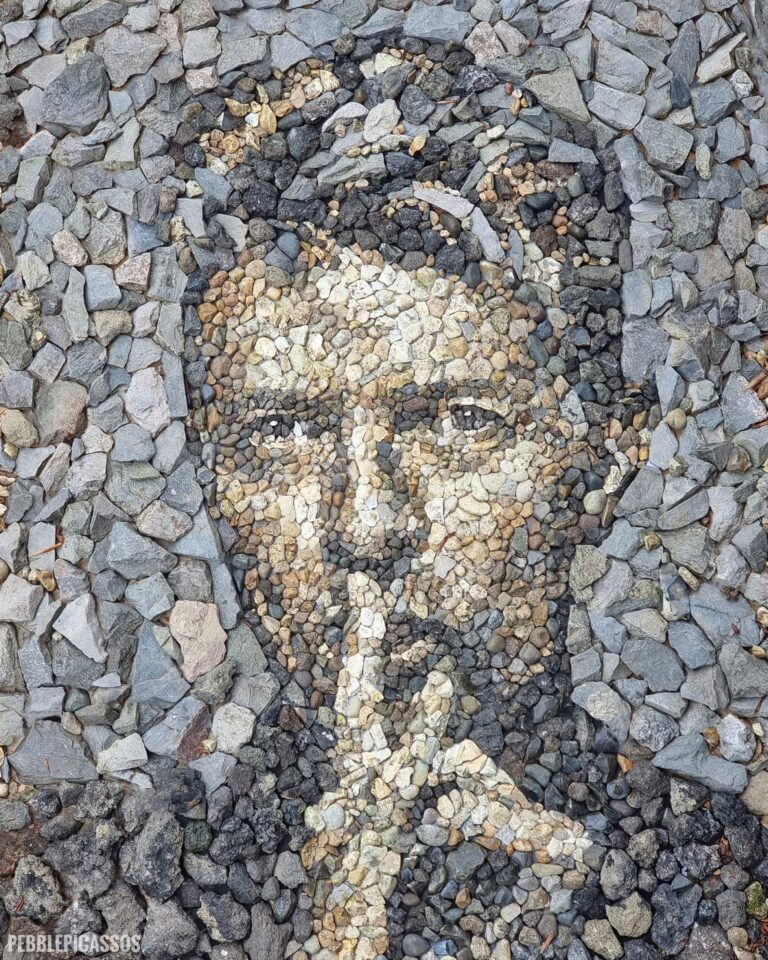

Masterpiece is no overstatement when it comes to Bateman’s compositions. A massive likeness of Frida Kahlo, for example, might be mistaken for a painting rather than an arrangement of rocks, if one were to squint their eyes at a photo of the portrait. The shading of her lips is that subtle, the expression in her eyes that uncanny.

Formerly an art lecturer, Bateman began working with pebbles while exploring the use of natural materials for a variety of environmental art workshops he’d developed. He found that land art fit perfectly with his lifestyle: He’s a minimalist who loves to travel. Currently based in Chiang Mai, Thailand, he’s also created pieces in Indonesia and the U.K.

As art supply stores and studios aren’t really part of the picture for Bateman, who uses the handle PebblePicassos on Instagram, location and materials are integral parts of his process.

“Traditional mosaic uses uniform squares called ‘tessera,’ but my pebble portraits use only natural found stones — I never cut or color pebbles,” he explained. “This means stone selection is vital, but it is a very mindful activity, connecting with the local environment. I also consider the surface of the pebbles, things as subtle as texture can determine masculine and feminine characteristics.”

When he comes across level areas with stones nearby, he’ll drop a pin on Google Maps so he can return to create a piece. At places he knows he’ll be revisiting, he buries pebbles to use later. But he can’t rely on circumstance alone for his materials: “A bit like a squirrel with his acorns, I usually have a pocket full of stones,” he shared, “but I use stones on location as much as possible.”

When it comes to deciding who to capture in any particular piece, Bateman rarely sets his mind on something specific. “There are a wide variety of influences on the work,” he wrote. “I get hundreds of requests but the final choice is usually determined during meditation. It is not that I align with the political or spiritual ideologies of the subject, they have simply become prominent in my consciousness for one reason or another. Sometimes they are inspiring people or even animals I have encountered on my travels.”

Once inspiration has struck, Bateman starts looking at the world through the lens of what he’ll need to create the piece, noting certain locations, weather conditions, and developing a color palette in his mind. Then he’ll begin collecting pebbles. The first stones he sets down are always the eyes, he said.

Though the portraits take hours to make, for Bateman, the process is meditative. He purposely works for long stretches at a time without stepping up to move around, finding that the prolonged concentration puts him in a state of flow.

“It is like being able to control a tiny part of life,” he said. “In a world where I have no control, I can choreograph this brief dance with the stones and find peace in the process.”

Share to: