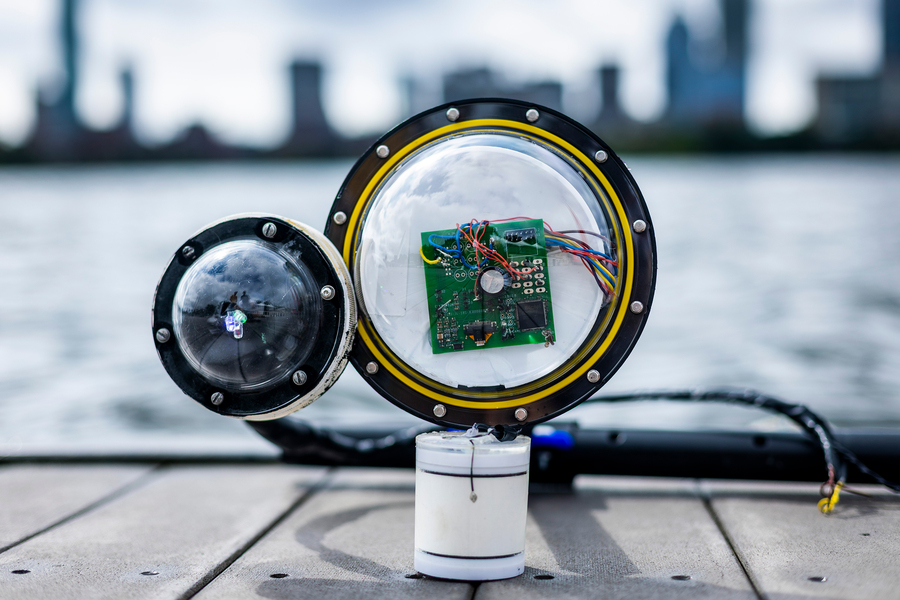

Engineers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have built a battery-free, wireless underwater camera that can travel up to 130 feet below the surface, a groundbreaking device that may one day be capable of collecting never-before-seen images of the deep sea.

We know more about the surface of Mars than Earth’s ocean floors. To date, only 5% of the ocean has been explored by humans, despite the fact that it is the biggest ecosystem on the planet. That’s because the deepest ocean floors — called “the hadal zone” after Hades, the ancient Greek god of the underworld — can be an unforgiving place for technology.

MIT researchers recognized that the high cost of powering an underwater camera is a major roadblock in wide-scale ocean exploration. Their solution is a battery-free, wireless underwater camera that is said to be 100,000 times more energy-efficient than other underwater cameras developed previously — it is completely unmanned by explorer or ship, and could survive for weeks on end.

Using soundscape as its energy source, the camera can take color photographs, even in dark areas, and transmit that data to researchers wirelessly. Per a press release, “It converts mechanical energy from sound waves traveling through water into electrical energy that powers its imaging and communications equipment,” noting that sound waves can come from any source, such as a ship or marine life.

To capture color images, red, green, and blue LEDs are utilized. “Even though the image looks black and white, the red, green, and blue colored light is reflected in the white part of each photo,” the press release explains. “When the image data are combined in post-processing, the color image can be reconstructed.”

Furthermore, the camera can operate for weeks before it loses power, allowing researchers to study little-known species — and perhaps even discover new ones.

Fadel Adib, associate professor in the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science and director of the Signal Kinetics group in the MIT Media Lab, noted that climate monitoring is an additional and equally groundbreaking prospective way to use this advanced technology.

“We are building climate models, but we are missing data from over 95% of the ocean. This technology could help us build more accurate climate models and better understand how climate change impacts the underwater world,” Adib said in a statement.

Researchers tested the camera in several environments and on different subjects, including plastic bottles floating in a pond, an African starfish, and the underwater plant Aponogeton ulvaceus.

The scientists, who published their results in Nature Communications, want to improve on this prototype by increasing the camera’s memory and range. The device has successfully transmitted data from depths of 130 feet, a mere fraction of the miles upon miles that have yet to be explored. But once the technology is perfected, Adib told CBC, it will have serious implications for ocean exploration and climate change research.

“We want to be able to use them to monitor, for example, underwater currents, because these are highly related to what impacts the climate,” he said. “Or even underwater corals, seeing how they are being impacted by climate change and how potentially intervention to mitigate climate change is helping them recover.”

Pingback: Researchers Created Sound That Can Bend Itself Through Space, Reaching Only Your Ear in a Crowd - Usernames Ideas