For those of us who aren’t scientists, a chance encounter with an inert ground-dwelling rodent probably wouldn’t turn into a decades-long quest for knowledge about the animal that is now linked with making space exploration safer for humans. But in 1992, for Kelly Drew, a professor of chemistry and biochemistry at the University of Alaska, that’s how it all started, after a colleague unexpectedly placed a hibernating squirrel in her hands.

Several decades later, with funds awarded through a NASA Space Grant, Drew, aided by students and interns, has parlayed her long-term study of Arctic ground squirrels into developing applications relevant to humans, according to a recent NASA press release. By studying the physiology of the ground squirrels — animals that hibernate annually for eight to nine months — Drew has been learning how their bodily processes might be mimicked in humans.

While hibernating, these little animals are “slowing their metabolism so much that their body temperature can drop below freezing without suffering the usual side effects like freezing, muscle loss, or loss of bone density during the long winter months,” the press release explains.

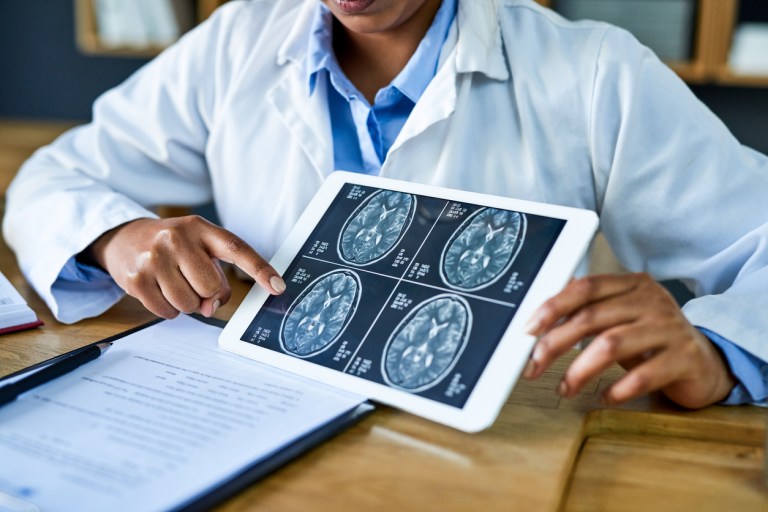

Much of Drew’s primary research focus has been on hibernation in humans for the development of neurocritical care techniques and medications, in particular. When a patient has suffered a critical medical event, like a stroke or heart attack, every minute counts — and placing patients into a safe medically-induced state of hibernation can make all the difference in securing a positive outcome while transporting a patient to the hospital for life-saving care.

As it turns out, the concept of human hibernation is also important when it comes to long-term space missions.

NASA, the Chinese National Space Administration, and SpaceX have all set their sights on being the first to put humans on Mars within the next two decades, but to say the task is a momentous one would be a profound understatement. Mars is roughly 140 million miles from Earth, and sending even a small crew of four astronauts on an 1,100-day roundtrip mission would require food, supplies, tools, adequate fuel, and a fully-operational spaceship to carry everything, all of which would likely exceed 330 tons in weight, according to WIRED. Solving the riddle of how to power such a mission has thus far eluded those focused on the task. To put things in perspective, the biggest payload (or cargo) ever carried to Mars has been the Perseverance rover; yet, the outlet reports, the weight of the food alone needed to sustain four astronauts on a manned mission would weigh 10 times as much as the rover.

In 2013, John Bradford, an executive at SpaceWorks, secured funding from NASA’s Innovative Advanced Concepts program to study the feasibility of human torpor (in other words, human hibernation). By Bradford’s calculations, the weight of “life-support resources” needed for a trip to Mars could be radically reduced, by as much as 60%, if astronauts were able to make the trip while kept in a state of torpor.

Some scientists have speculated that the human body in a state of suspension might also be better equipped to ward off many health hazards that astronauts are subjected to in space, including exposure to radiation and the psychological strain of a long trip in extremely tight quarters. Working off the realization that a number of species successfully hibernate every winter and, while doing so, are able to minimize their need for food and air during the process, Bradford eventually began to turn to the work of hibernation researchers for inspiration.

In 2015, Bradford’s and Drew’s paths invariably converged, and he approached her with an intriguing offer: become the chief hibernation consultant at SpaceWorks. By 2018, Drew and her research on hibernating squirrels were central to the mission set forth in SpaceWorks’ final report from phase two of its human-torpor project, according to WIRED — a report that estimates NASA might be positioned to test various hibernation technologies on humans by 2026.

The challenges to developing a safe and effective human hibernation technique are substantial, but given the degree of innovation that would be made possible in both medicine and space travel alike, the field of study continues to draw the attention and talents of science’s best and brightest.

RELATED: