This article was originally written by Stephen Beech for SWNS — the U.K.’s largest independent news agency, providing globally relevant original, verified, and engaging content to the world’s leading media outlets.

More than 5 million people worldwide are impacted by geographic atrophy due to age-related macular degeneration, the leading cause of irreversible blindness. There’s previously been no treatment for the condition — but in a new landmark trial, scientists restored vision to patients for the first time.

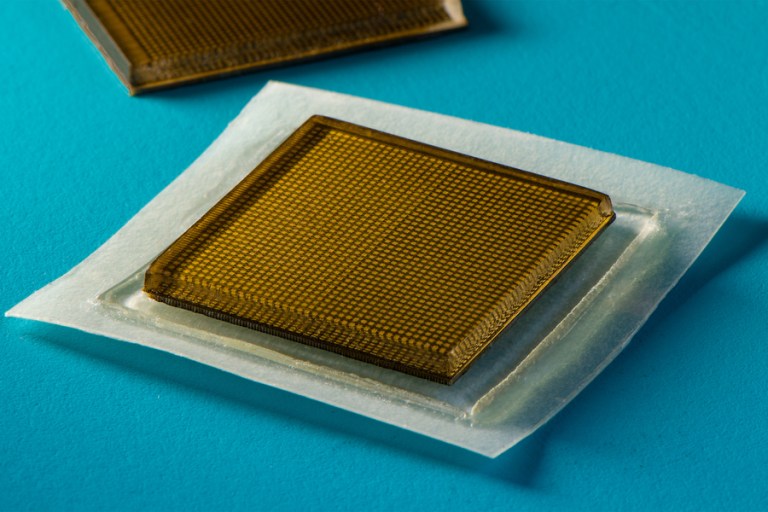

It’s all thanks to PRIMA, a tiny eye implant half as thick as a human hair. When paired with augmented-reality glasses, the pioneering device is the first-ever to enable people to read letters, numbers, and words with an eye that had lost its sight.

“In the history of artificial vision, this represents a new era,” Mahi Muqit, who led the U.K. arm of the trial, said in a news release. “Blind patients are actually able to have meaningful central vision restoration, which has never been done before. Getting back the ability to read is a major improvement in their quality of life, lifts their mood, and helps to restore their confidence and independence.”

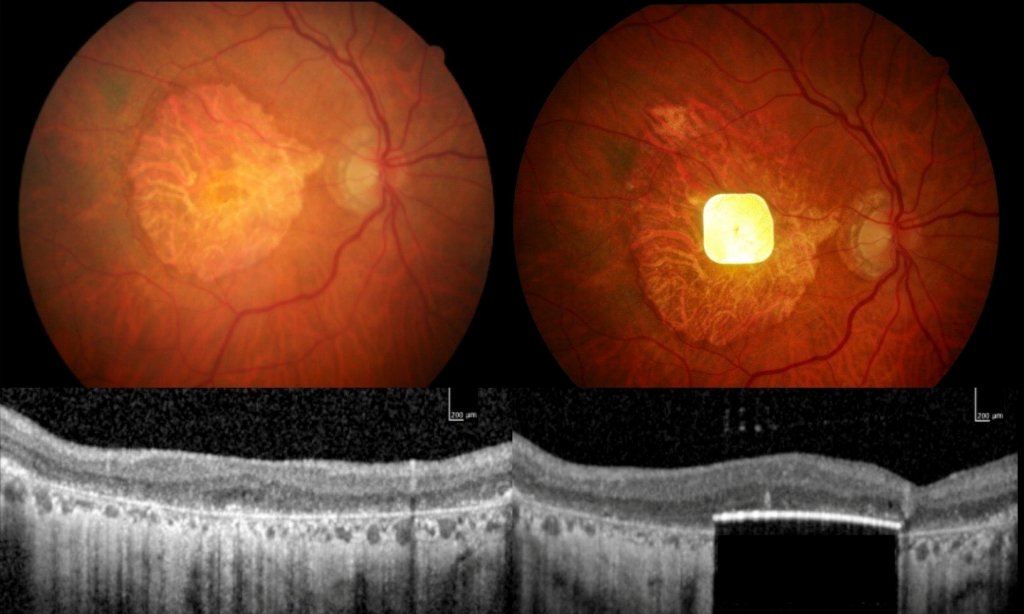

Dry age-related macular degeneration, known in brief as dry AMD, is a slow deterioration of the cells of the macula — a small area at the center of the retina in the back of the eye — over many years, as the light-sensitive retinal cells die off. Most people with dry AMD can experience a slight loss of central vision. But through the process of geographic atrophy, or GA, the condition can progress to full central sight loss in the eye, as the cells die and the central macula melts away.

For the recent trial, 38 patients at 17 hospital sites across five countries tested PRIMA. All the patients had lost complete central sight in the treated eye before receiving the implant, leaving only limited peripheral vision.

The procedure involves a vitrectomy, during which the eye’s vitreous gel is removed from between the lens and the retina, before the surgeon inserts the ultra-thin microchip, which is shaped like a SIM card and measures just 2 millimeters by 2 millimeters. The chip is placed under the center of a patient’s retina by creating a “trapdoor” into which it is posted.

“The PRIMA chip operation can safely be performed by any trained vitreoretinal surgeon in under two hours — that is key for allowing all blind patients to have access to this new medical therapy for GA in dry AMD,” Muqit said.

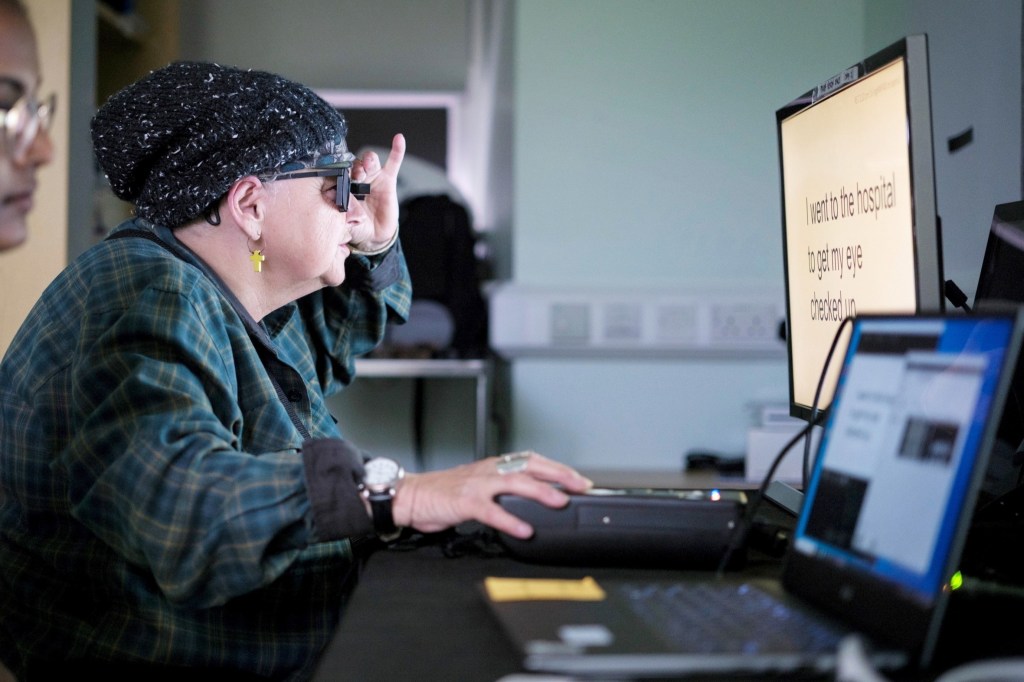

Once the eye has healed, around a month or so after the operation, the new chip is activated. The patient uses augmented-reality glasses with a video camera, which are linked to a pocket-size computer attached to their waistband. The camera captures visual scenes and projects them as an infrared beam directly across the chip.

From there, the computer’s AI algorithms process the information, which is then converted into electrical signals that pass through the retinal and optical nerve cells into the brain, where they’re interpreted as vision. The patient uses their glasses to focus and scan across the main object in the projected image from the video camera, deploying a zoom feature to enlarge text. Each patient in the trial went through an intensive rehab program spanning several months to learn to interpret the signals and start reading again.

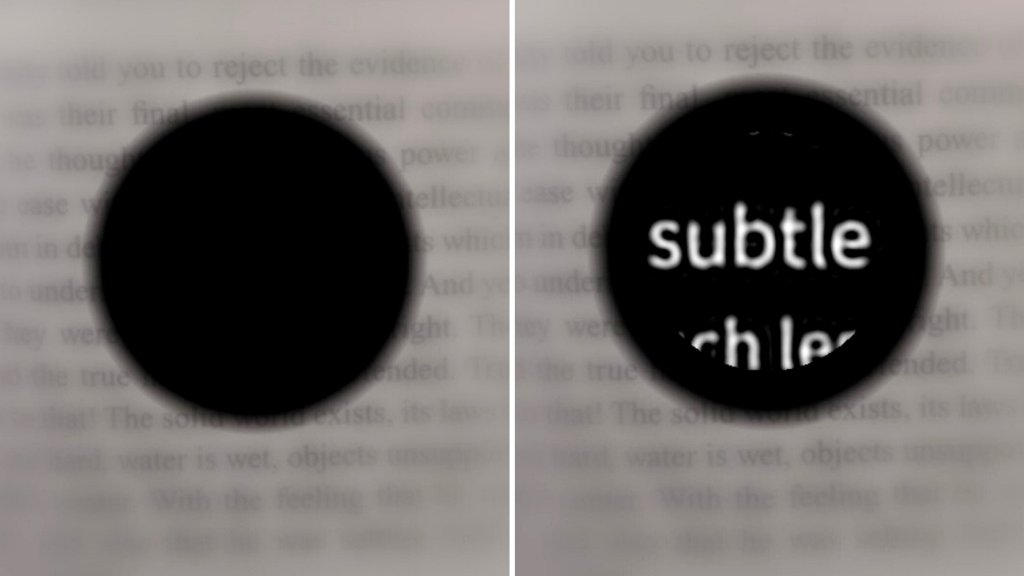

“The rehabilitation process is key to these devices,” Muqit said. “It’s not like you’re popping a chip in the eye and then you can see again. You need to learn to use this type of vision. These are elderly patients who were no longer able to read, write, or recognize faces due to lost vision. They couldn’t even see the vision chart before. They’ve gone from being in darkness to being able to start using their vision again, and studies have shown that reading is one of the things patients with progressive vision loss miss most.”

In the trial, 84% of participants were able to read letters, numbers, and words at home using their prosthetic. Those treated with the 0.03 millimeter thick-device could also read, on average, five more lines on a vision chart, despite the fact that some participants couldn’t even see the chart before surgery. The researchers didn’t observe any significant decline in the trial participants’ existing peripheral vision.

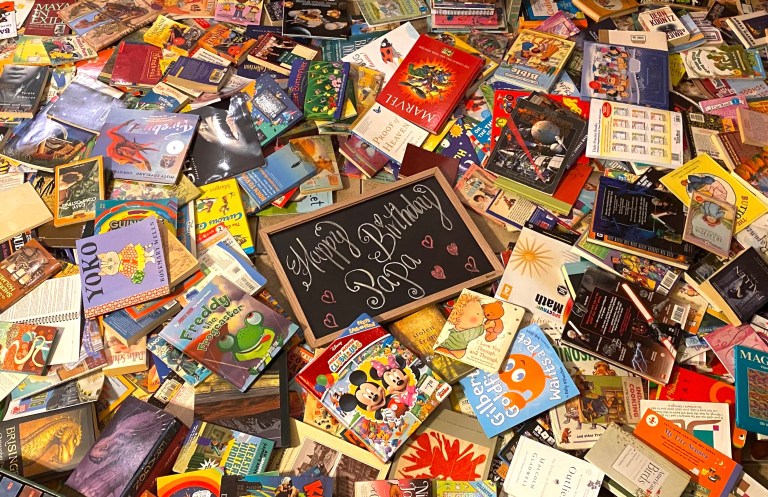

“I wanted to take part in research to help future generations,” said Sheila Irvine, a patient in the trial at London’s Moorfields Eye Hospital. “My optician suggested I get in touch with Moorfields. Before receiving the implant, it was like having two black discs in my eyes, with the outside distorted. I was an avid bookworm, and I wanted that back. I was nervous, excited, all those things.”

Though she didn’t feel pain during the operation, Irvine noted that she was aware of what was happening — and is happy with the outcome. “It’s a new way of looking through your eyes, and it was dead exciting when I began seeing a letter,” she said. “It’s not simple, learning to read again, but the more hours I put in, the more I pick up. The team at Moorfields has given me challenges, like ‘look at your prescription,’ which is always tiny. I like stretching myself, trying to look at the little writing on tins, doing crosswords. It’s made a big difference. Reading takes you into another world, I’m definitely more optimistic now.”

Published in The New England Journal of Medicine, the findings pave the way for approval to market the new device.

“My feeling is that the door is open for medical devices in this area, because there is no treatment currently licensed for dry AMD — it doesn’t exist,” Muqit said. “I think it’s something that, in future, could be used to treat multiple eye conditions.”

Dr. José-Alain Sahel, senior author of the study and director of the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine’s Vision Institute, also hopes to make a significant difference in the lives of blind people. He said in a statement that “while we can’t yet restore full 20/20 vision with the implant alone,” he and his colleagues “are investigating methods that could further improve people’s quality of life and take them above the threshold for legal blindness.”

RELATED: Like “Braille for Sports,” This Handheld Tool Lets Blind Fans Watch a Game Through Their Fingers