“Smile in your liver,” Bali medicine man Ketut Liyer urges Elizabeth Gilbert in the author’s iconic memoir, Eat, Pray, Love. The sentiment is heartwarming, but it likely left some readers wondering: How do you smile, or express any emotion at all, in your liver?

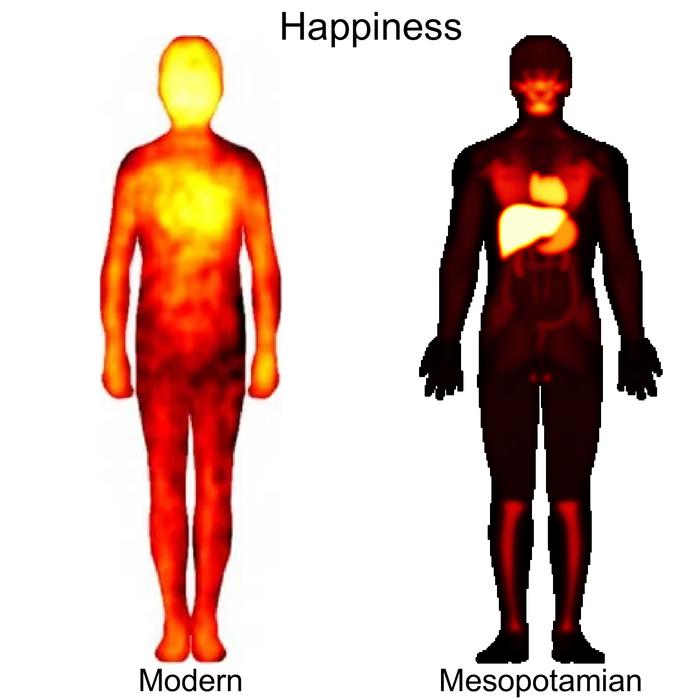

While many modern-day humans aren’t familiar with this concept, the ancient Mesopotamians certainly were. Thanks to new research from Finland’s Aalto University, we now have a better understanding of how our ancestors in this region associated emotions with different parts of the body. The Mesopotamians observed anger in their legs and feet, while they felt happiness in — you guessed it — their livers.

Figure: Modern/PNAS: Lauri Nummenmaa et al., Mesopotamian: Juha Lahnakoski.

“If you compare the ancient Mesopotamian bodily map of happiness with modern bodily maps [published by fellow Finnish scientist, Lauri Nummenmaa and colleagues a decade ago], it is largely similar, with the exception of a notable glow in the liver,” cognitive neuroscientist Juha Lahnakoski said in a news release.

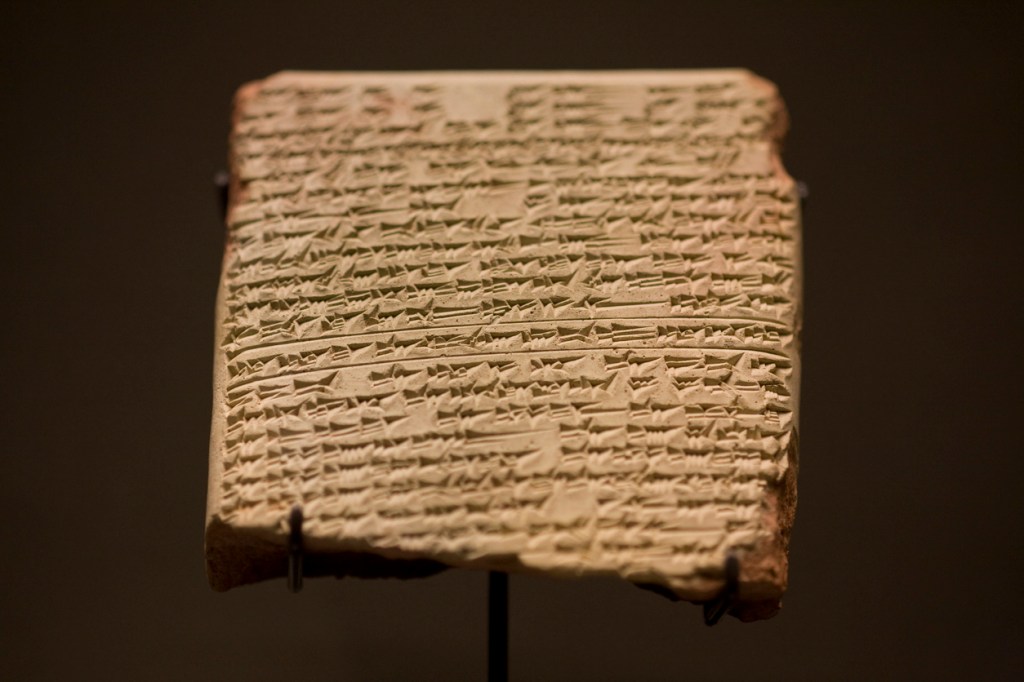

To glean this information, the research team analyzed 1 million words of the Semitic language Akkadian, written on clay tablets in cuneiform from 934-612 B.C. They looked for “consistent relationships between linguistic expressions related to both emotions and bodily sensations,” per the Dec. 4 study.

For instance, the ancient writers frequently described feeling “open,” “shining,” or “full” in the liver when indicating happiness. Then, the researchers calculated statistical regularities between the emotional verbiage and language referring to body parts.

The result? Bodily sensation maps that display patterns for 18 separate emotions specified by the Mesopotamians, including surprise, envy, and pride. The researchers concluded that the ancient humans related sympathy and schadenfreude (a positive reaction to someone else’s misfortune) to the chest, throat, and lower face; desire to the liver, heart, and legs; and fear to everywhere except the hands and upper head.

“Even in ancient Mesopotamia, there was a rough understanding of anatomy, for example the importance of the heart, liver, and lungs,” University of Helsinki professor Saana Svärd explained in the release.

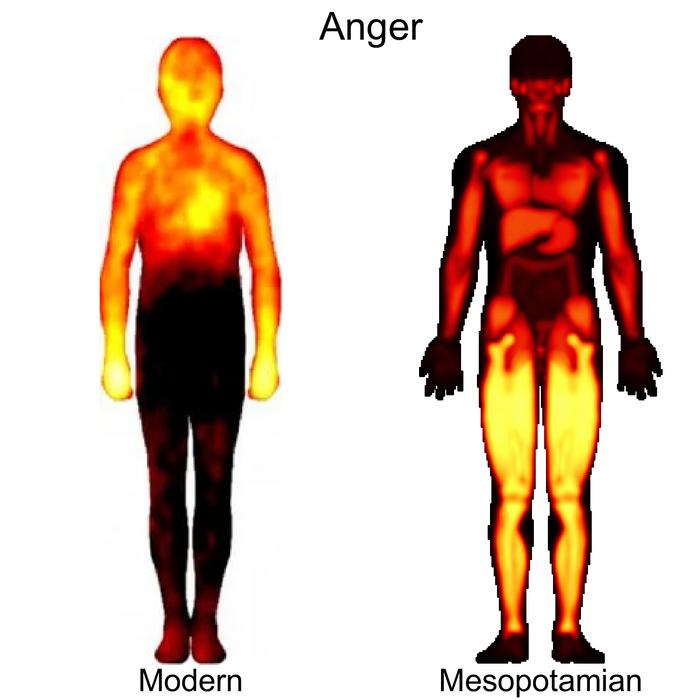

Aside from differences around happiness, another aspect of this data varies widely from analyses of where emotions are felt in the body today. Participants in the 2014 study by Nummenmaa reported experiencing anger primarily in the head, torso, and arms, which lines up with terms like “boiling over,” “seeing red,” and being a “hot head” that modern English speakers commonly use to express the emotion. But these descriptors starkly contrast with those from our Mesopotamian ancestors, who referenced anger in relation to the opposite end of the body.

Figure: Modern/PNAS: Lauri Nummenmaa et al., Mesopotamian: Juha Lahnakoski.

However, the team behind the 2024 research added that as accurate as their data is, emotions are subjective enough that it’s tough to make definitive conclusions about how they’re felt for humans as a whole. “It remains to be seen whether we can say something in the future about what kind of emotional experiences are typical for humans in general,” Svärd noted, adding, “we have to keep in mind that texts are texts and emotions are lived and experienced.”

And yet, because this is the first instance of researchers using quantitative analysis of ancient Near Eastern texts to associate emotions with body parts, the work opens the door to further exploration into intercultural differences (and similarities) in emotional experiences across time.

RELATED: After 2,500 Years, a Ph.D. Student Has Solved an Ancient Grammatical Puzzle