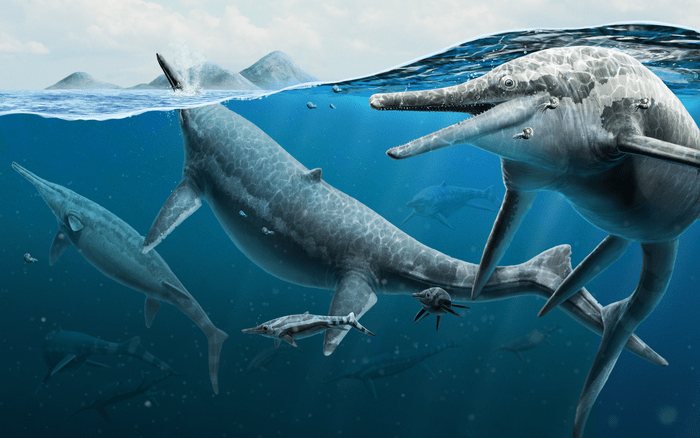

In the middle of Nevada’s vast desert there’s a 200-million-year-old rich fossil bed, where many “school bus-sized” ichthyosaurs are petrified in stone.

The remains of these 50-foot-long, ancient marine reptiles (Shonisaurus popularis) have been found over the course of half a century, but the findings have perplexed paleontologists since their discovery — specifically why their remains were found in such close proximity in an area that didn’t appear to provide them with a foodsource when they were alive. Now, a team of scientists — including researchers from the University of Utah, Smithsonian Institution, and Vanderbilt University — have pieced together evidence, found at Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park (BISP) within Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest, and suggested that the “quarry 2” site could have been a birthing ground for these prehistoric creatures. A team of researchers from the Smithsonian Institution and various universities recently published their findings in Current Biology.

“There are so many large, adult skeletons from this one species at this site and almost nothing else,” study co-author and Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History curator Nicholas Pyenson said in a press release. “There are virtually no remains of things like fish or other marine reptiles for these ichthyosaurs to feed on, and there are also no juvenile Shonisaurus skeletons.”

According to the press release, researchers previously hypothesized that the marine animals — predators that resemble large, chunky dolphins — may have died in a mass stranding event, a phenomenon that affects modern whales today. Although the majority of specimens are adult ichthyosaurs, fossils of embryos and newborns were also found in the quarry.

“Once it became clear that there was nothing for them to eat here, and there were large adult Shonisaurus along with embryos and newborns but no juveniles, we started to seriously consider whether this might have been a birthing ground,” said lead author Neil Kelley.

Researchers pored over the site — a tourist attraction in the Silver State — equipped with modern methods to try and solve the mystery of the quarry.

The team used 3D scanning and geochemistry along with traditional paleontological perseverance, including analyzing archival materials, photographs, maps, field notes and “drawer after drawer of museum collections for shreds of evidence that could be reanalyzed” for the study.

“We present evidence that these ichthyosaurs died here in large numbers because they were migrating to this area to give birth for many generations across hundreds of thousands of years,” said Pyenson. “That means this type of behavior we observe today in whales has been around for more than 200 million years.”

The findings also suggest that ichthyosaur has more in common with today’s blue and humpback whales than was previously thought. Just as modern-day whales make migrations thousands of miles across oceans to breed where predators are scarce, so did the ichthyosaur; this new research suggests a fundamental link between prehistoric and present-day species.