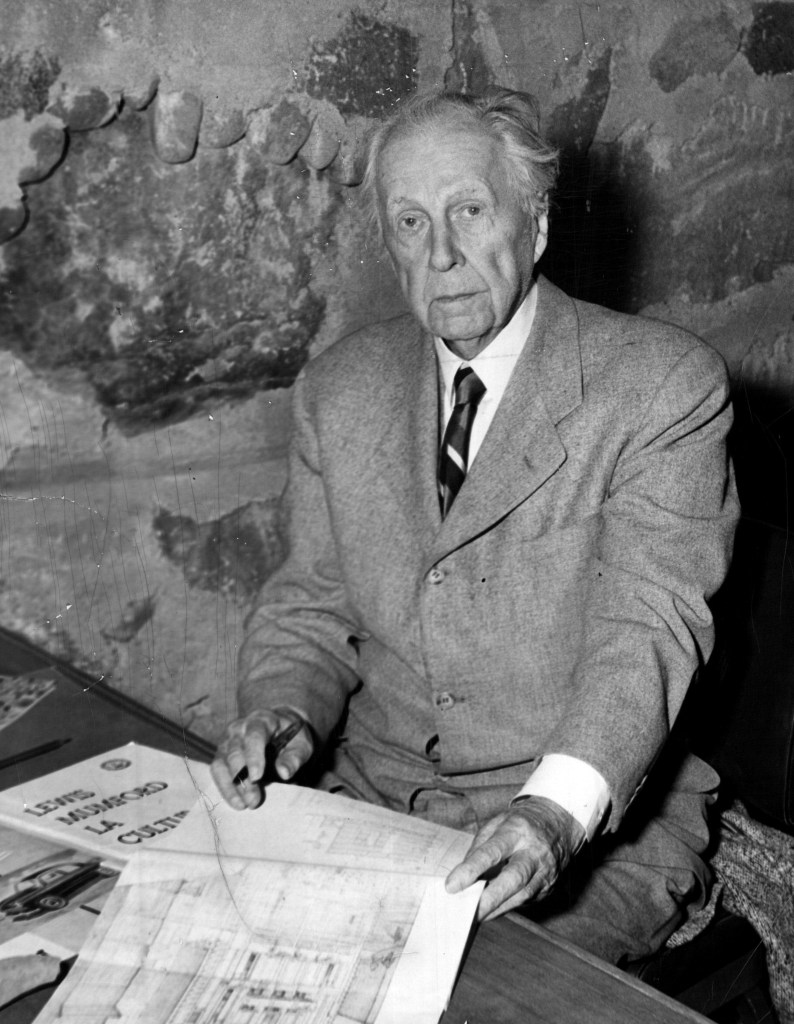

How many architects can you name off the top of your head? Whether that list is on the long or short side, Frank Lloyd Wright likely nabbed a spot. Even if you don’t know much about the man himself, we’d bet the iconic spiral featured in one of his most famous works, the legendary Guggenheim Museum in New York City, has a firm foothold in your architectural knowledge base.

That’s no small thing, considering Wright died April 9, 1959, at age 91. But more than a half-century after his passing, he remains one of the most well-known architects of our time, and his houses in particular have continued to create “the blueprint for so much of American architecture,” according to Architectural Digest. And yet throughout his life, Wright had an even bigger purpose in mind.

“The mission of an architect is to help people understand how to make life more beautiful, the world a better one for living in, and to give reason, rhyme, and meaning to life,” he said, as noted on the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation website.

Below, we dive into four of the whopping 532 buildings that were constructed from his celebrated designs. Read on for some of the highlights of the architect’s seven-decade career.

Taliesin West

Open, expansive desert extends beyond the borders of Taliesin West — the name that Wright gave to his winter home and school for his apprentices — in Scottsdale, Arizona. In a 1952 talk, the architect explained he regarded the desert as “the greatest lesson in construction,” per the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, adding: “The saguaro is the greatest example of a skyscraper that was ever built.”

In 1937, he and his apprentices built a structure primarily out of local rock set in wood, connected by a mixture made with cement and desert sand. Wright aimed to meld it with the natural surroundings as much as possible, designing low-slung buildings to mimic the vastness of the landscape. He created canvas roofs to offer plenty of light, and incorporated redwood beams because the material was easy to source.

In the winter, Wright and his students lived in Taliesin West, working, studying architecture, and learning other art forms. “I always think of Taliesin West as a laboratory for learning,” Jennifer Gray, vice president and director of the Taliesin Institute for the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, told Architectural Digest. “It was a very experimental place. It was constantly being changed and adapted. This makes Taliesin West a particularly compelling place to come and engage with Wright’s ideas and theories.”

Marin County Civic Center

Wright’s last commissioned work sits squarely in downtown San Rafael, California, less than an hour’s drive from San Francisco. As its name suggests, the Marin County Civic Center is a government building, but it’s also a setting for two science fiction movies, THX 1138 and Gattaca — which offers somewhat of a hint as to its appearance.

The structure features a galactic-looking blue-roofed sphere intended to blend in with the sky, along with pink stucco walls and a 172-foot-tall gold spire with a TV antenna that jolts up toward the clouds. “We know that the good building is not the one that hurts the landscape, but is one that makes the landscape more beautiful than it was before that building was built,” Wright said, per the County of Marin.

He continued: “In Marin County you have one of the most beautiful landscapes I have seen, and I am proud to make the buildings of this county characteristic of the beauty of the county.” Sadly, the architect didn’t live to see construction begin on this particular work. A month after his death, his third wife, Olgivanna Lloyd Wright, signed a new contract between the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation and Marin County on his behalf, and two of the Foundation’s architects took up the mantle.

Guggenheim Museum

No list of illustrious Wright works is complete without the Guggenheim: a 4,750-square-meter inverted ziggurat tower in the Big Apple that now houses around 8,000 artworks in its permanent collection. But while the museum says it was “immediately recognized as an architectural icon” when it opened in October 1959, it took quite a journey to get it there.

The Guggenheim under construction in 1957.

Wright was originally commissioned to design the building in 1943, and it was initially meant to serve as the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation’s Museum of Non-Objective Painting. In response to then-museum director Hilla von Rebay saying she sought “a fighter, a lover of space, an originator, a tester, and a wise man” to create the structure, Wright pledged to “make the building and the painting an uninterrupted, beautiful symphony such as never existed in the world of art before,” as cited by the Foundation.

For the next 16 years, obstacles like Guggenheim’s death and increasingly expensive building materials delayed the project until construction finally began in 1956. The museum officially opened six months after Wright died — but his commitment to nature can still be seen in its spiral ramp and rotunda skylight designs, believed to have been inspired by nautilus shells and spider webs.

Frederick C. Robie House

Compared to the unique spiraling tower of the Guggenheim, Chicago’s Frederick C. Robie House appears slightly more unassuming at first glance. But the nevertheless sizable edifice, which has been called “the most important building of the 20th century” and “the greatest work of architecture America has produced,” per Rost Architects, inspired an entire style of architecture.

Completed in 1910, the structure emphasizes horizontality and features cantilever low roofs, as well as a simple, open floor plan that allows for plenty of natural light. Its design, meant to reflect the sweeping plains of the Midwest, signified a departure from the typical American European-style homes of the time to the more modern Prairie style — which became known as the first truly American style of architecture, according to The Spruce.

Frederick Robie, for whom the house was built, ran into financial issues and sold his home after only 14 months of living in it. When the structure was nearing demolition, Wright made a plea to salvage it, claiming it was a “cornerstone in American architecture,” per the Foundation. The house was saved, and was honored in 1991 by the American Institute of Architects as one of the 10 most significant structures of the 20th century.

Can’t get enough of Wright’s innovative buildings? Embark on virtual voyages to a “hidden woodland utopia” and peaceful Connecticut sanctuary designed by the architect.

RELATED: Architect Creates Stunning, Photorealistic Renderings of Unrealized Frank Lloyd Wright Buildings