If you had a hammer, you could hammer in the morning, as the old song goes. But what would you do if you had 10,000 hammers? You’d open a hammer museum, of course. At least, that’s what collector Dave Pahl did in his tiny town of Haines, Alaska.

Small and unassuming — aside from the giant 19-foot-tall hammer standing in front of it — the Hammer Museum sits on a green lawn and features a backdrop of Alaskan mountains. Not to be confused with Los Angeles’ Hammer Museum, which exhibits art and is named after its founder, this one has a simple mission: to preserve the history of hammers.

“There’s something for everybody here at the Hammer Museum,” Pahl told Smithsonian Magazine, emphasizing the ubiquitousness and necessity of the household tool. “Everybody uses a hammer, but a lot of us don’t even realize how often, or where we’d be without it.”

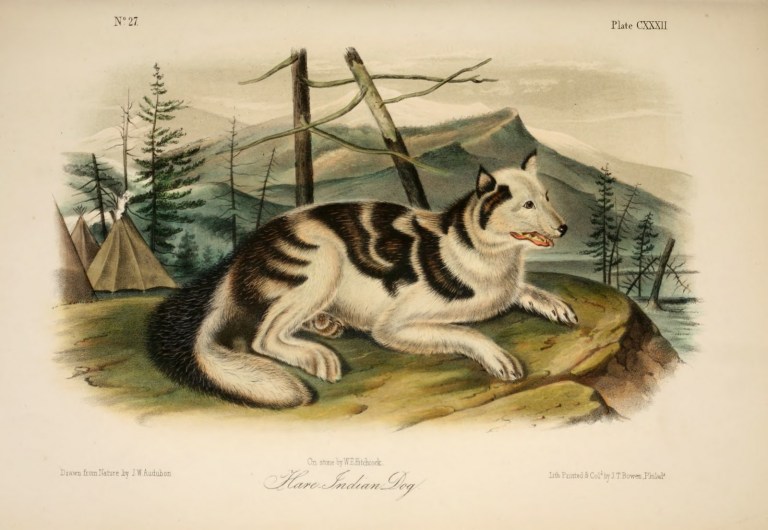

More than 2,000 hammers are currently displayed, representing the long and storied journey the instrument has taken to your toolbox. Rock hammers believed to have helped build the Pyramid of Menkaure in Egypt, Native American mallets, a meat tenderizer from the 1940s, hammers bank tellers once used to cancel checks in the 1880s, and more line the walls of the four-room museum. Another 8,000 are kept in storage.

After moving to Alaska in 1980 to become a homesteader, Pahl began collecting tools he needed to “live off the land.” Eventually, though, he found himself with far more hammers than any one man requires. “Family vacations were hammer hunting,” he said, adding that he “was getting a lot of pressure from [my wife] Carol to get some of these hammers out of the house. She was getting tired of dusting.” But Carol eventually got into collecting too, according to the museum’s website. Her personal collection of glass hammers is currently on display.

Considered the world’s first hammer museum when it opened in 2002, the shrine has since sparked similar iterations — one in Kentucky, another in Lithuania. In 2004, it became a nonprofit organization, even developing its own summer internship program, and Dahl has firmly established himself as an expert. A curator for the National Museum of American History once sought Pahl’s help in identifying hammers in the Smithsonian’s collections, Smithsonian reports, and the History Channel has reached out to inquire about the proper hammers to use in reenactments.

Pahl’s latest endeavor is the 200-page hammer “bible” he self-published in August, but he has blueprints for another idea that he’s constructing. Last month, he shared with Haines’ own Chilkat Valley News that he’s hoping to release a hammer day planner for 2023. “There’s a hammer for every day of the year,” he said.