Like a maestro guiding an orchestra through the movements of a symphony, the traffic light ushers drivers through the motions of transit, from the decrescendo of yellow to the precipitato of green. You might not think twice about three-phase signals on your daily commute, but they’ve saved countless lives since their inception over a century ago — and there’s one man in particular we can thank for patenting the invention.

Although the first hand-operated traffic signals appeared in 1868, these devices had only two settings for “stop” and “go.” Their susceptibility to human error — and the absence of a third position (the equivalent of today’s yellow light) — meant intersections were chaotic and dangerous. Upon witnessing a collision between a horse-drawn carriage and an automobile, Garrett Morgan decided to change that. Like many Black innovators of his day, Morgan’s name isn’t well-known, but his ideas have helped shape the modern world as we know it.

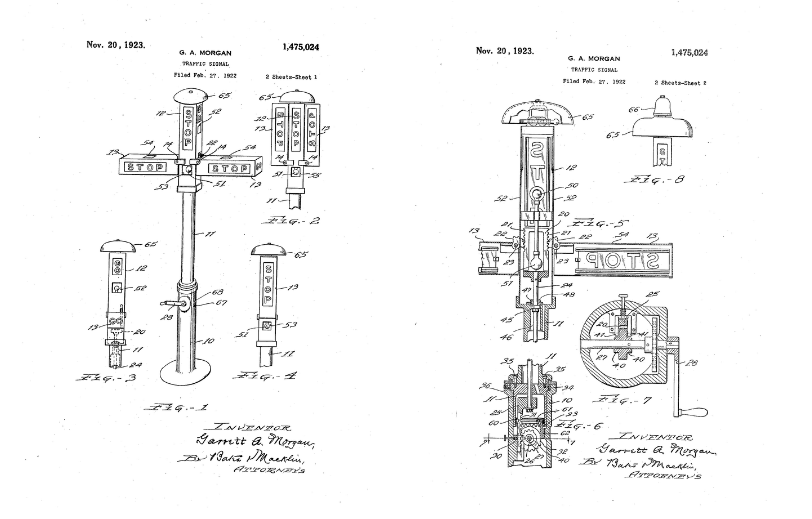

Morgan’s traffic signal was a T-shaped pole with three settings: stop, go, and an all-directional stop position. The first two positions, stop and go, instructed traffic traveling in a particular direction (e.g., north-south) to go, while travelers in another (e.g., east-west) waited. Its third, all-stop position, with all three arms upright, instructed traffic to stop in all directions, ensuring the intersection was clear before allowing traffic to proceed. Besides establishing order for cars and carts, the all-stop signal allowed pedestrians to cross safely.

During the evening, or when traffic was sparse, Morgan’s invention could stay in a half-mast position, serving as the equivalent of a blinking yellow today.

“His patent for a mechanical traffic signal contained an intermediate step between ‘stop’ and ‘go’ that cleared the intersection,” Rebekah Oakes, a U.S. Patent and Trademark historian, told CNN. “Today, we know it as the caution light or yellow light.”

Other inventors are said to have ideated similar solutions, but Morgan — who called himself “the Black Edison” — was the first to receive a patent for his design on Nov. 20, 1923. He eventually sold the rights to his signal to General Electric for $40,000, the equivalent of around $733,000 in 2025.

The three-position traffic signal was just one of Morgan’s lifesaving innovations. When a blaze tragically killed 146 garment workers at the Triangle Shirtwaist factory in New York City on March 25, 1911, the nation was forced to reckon with glaring faults in fire safety codes and equipment — including the lack of gas masks. “Pulmonary complications following smoke inhalation account for about 77% of fire-related deaths, and it’s mostly from carbon monoxide poisoning,” Sumita Khatri, a pulmonologist at Cleveland Clinic, told Scientific American.

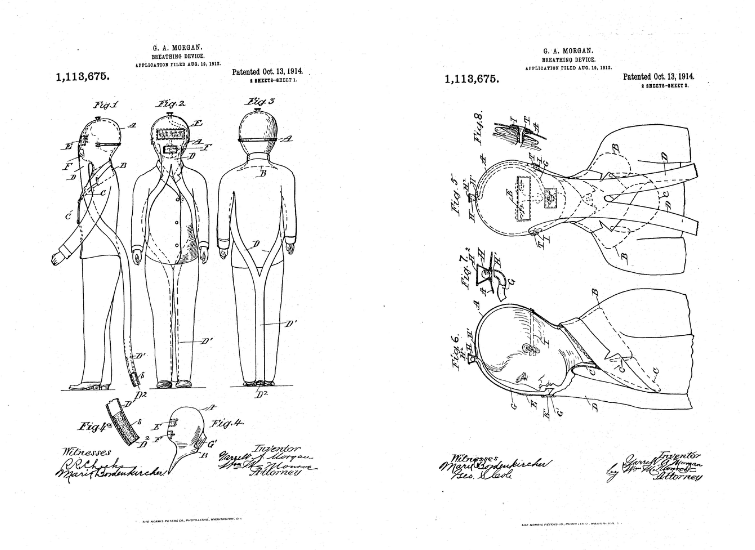

Morgan, who had worked as a sewing machine repairman before opening his own sewing equipment shop, developed a mask that could draw in clean air. Carbon monoxide, he realized, tends to hover at about eye level, whereas clean air usually remains near the ground. His hood, which draped over the wearer’s head like a beekeeper’s helmet, contained a long, tail-like intake tube that drew in clean air, allowing rescuers to breathe more safely.

Despite the device’s incredible potential, racism made selling it nearly impossible. Ultimately, he “created a theatrical scheme to bypass potential buyers’ bigotry. In 1914, he hired a white actor to pose as the inventor. Morgan then disguised himself, filled a tent with noxious smoke, and cued the actor to entertain the crowd as Morgan strapped on his breathing device and entered the tent — where he waited for nearly half an hour before emerging safely to an aghast audience,” Scientific American explained.

The demonstration caught the attention of reporters, and sales skyrocketed. Two years prior, he had patented the device, and in 1914, a refined model earned a gold medal from the International Association of Fire Chiefs, according to the Department of Transportation. In 1916, Morgan donned his mask again to rescue several men who had become trapped following a natural gas explosion in a tunnel they were digging beneath Lake Erie. And later, the mask protected World War 1 soldiers.

Morgan died in 1963, just before the Emancipation Proclamation centennial celebration, where he was honored as a pioneering citizen, according to The Lemelson Center. Although he didn’t receive all the recognition he deserved in his lifetime, he was nominated for a Carnegie Medal and Medal for Bravery for his heroism at Lake Erie in 1916, and just before his death, the U.S. government awarded him a citation for his traffic signal. Additionally, the National Inventors Hall of Fame and DOT have since honored his bravery and lifesaving ingenuity.

RELATED: 8 Tech Inventions That Transformed Our Daily Lives