Off Italy’s western coast in the Tuscan archipelago, just 22 miles from the city of Livorno, lies the tiny, often-windswept island of Gorgona. Visitors are drawn to its rugged beauty, and the isolated location promises not only a secluded getaway but also a behind-the-scenes glimpse at the unique work that goes on at the Gorgona Agricultural Penal Colony. The inmates there have free rein of the land from dawn until dusk, during which they’re permitted to tend gardens, raise livestock, and take part in the island’s winemaking process — from vine to grape to bottle.

With a total area of just under 1 square mile, Gorgona has a rich history. It was inhabited during the Roman era and served as a spiritual center throughout the Middle Ages, occupied by monks from Benedictine and Cistercian monasteries. The monks lived in isolation for centuries, cultivating the land surrounded by sweeping sea views. In 1406, the island was taken over by the powerful Medici family, who were responsible for some of the fortifications still standing today.

The monks had left Gorgona by 1777, and control of the island eventually fell into the hands of the Grand Duke of Tuscany, who established a prison there. When the Kingdom of Italy was formed in 1861, the prison stayed open after a deal was struck with the locals — they conceded that portion of the island in exchange for the prison taking care of their essential needs, a contract that remains valid even in 2025.

Visitors have long enjoyed the island’s extraordinary landscape of pine forests, olive groves, towering cliffs, and hidden coves. But because of its active prison, visits to Gorgona are tightly controlled; an authorized guide is mandatory, and the maximum number of daily visitors is capped at 100. Other strict protocols for those who wish to experience the island include obligatory police and prison forms to be filled out in advance, and absolutely no cameras or cell phones are permitted.

Gorgona’s penal colony winemaking tradition began in 2012, when then-prison director Maria Grazia Giampiccolo contacted over 100 Italian wineries to see if they’d be interested in helping the detention facility breathe new life into its vineyards. Just one person responded: Lamberto Frescobaldi of the famed Marchesi Frescobaldi wine dynasty, whose family has been making wine for over 700 years and 30 generations. He visited and surveyed the land, recognizing its potential — certainly for making wine but also for helping the inmates.

“I went there. The wine was terrible. The vineyards were terrible,” Frescobaldi told Food and Wine. “But I saw something in the human spirit. There’s the idea that wine can be a part of something greater, a part of the rehabilitation of these men.” It was then that Frescobaldi agreed to help revitalize the prison’s vineyard, launching an ambitious program that continues to teach the inmates the art and science of winemaking.

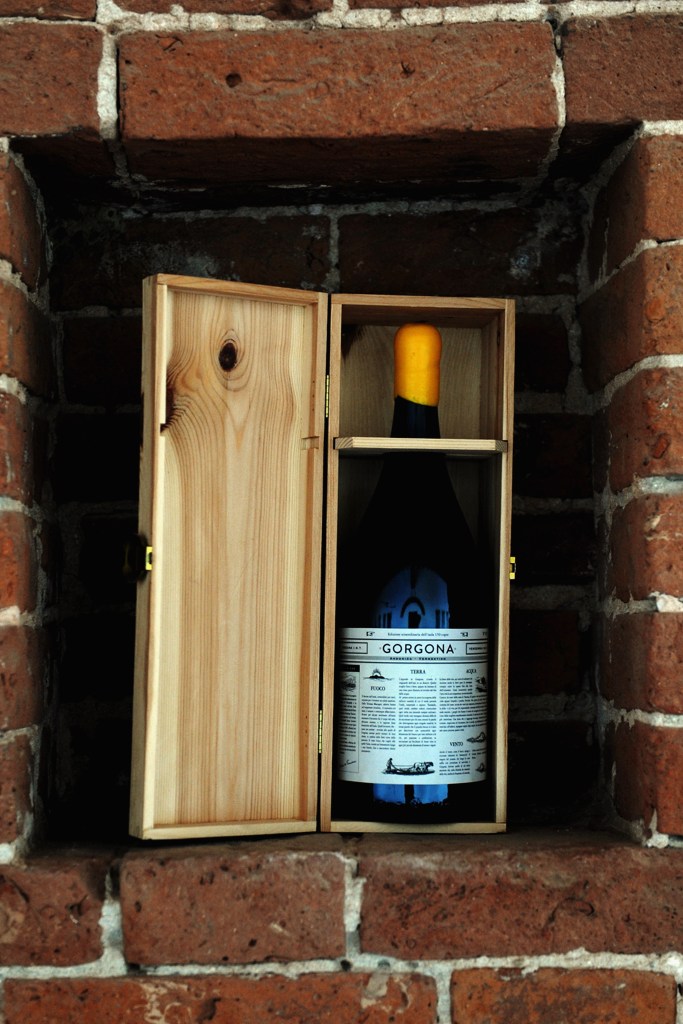

The collaboration between the penal institute and the Frescobaldi family produces two quality wines: the Gorgona Bianco Costa Toscana IGT, a bright blend of Ansonica and Vermentino grapes; and the Gorgona Rosso Costa Toscana IGT, a balanced, deep-red blend of Sangiovese and Vermentino Nero grapes. Only 9,000 bottles of each vintage are produced each year, and the wines are sought after for their quality and compelling human backstory. Most bottles retail for over $100.

But the real measure of success isn’t the quality of the wine or the number of bottles produced — it’s the number of lives that’ve been transformed since the beginning of the program. Inmates gain valuable employability skills and are paid decent salaries for their work. So far, 25 have gone on to work at other Frescobaldi estates after their release.

Even more remarkable about the men who’ve worked the vineyards during their incarceration is their recidivism rate, or the number of them who return to prison after release. The reoffending rate for these Gorgona inmates-turned-winemakers is 20%, a big difference from Italy’s main prison population: As of 2021, 62% of Italian inmates had a prior incarceration.

Speaking to Adventure.com, Frescobaldi’s son Carlo recounted an interaction Lamberto had with a child of one of the men. “One girl said proudly to my father, ‘my dad works for you in your vineyards.’”

Gorgona’s winemaking program remains strong; the vineyard has doubled in size since its inception, and the Frescobaldi family has an agreement to continue making wine there until 2044. The vines on this tiny island signify much more than agriculture — they also cultivate hope in an unlikely place, helping second chances to take root and flourish.

Frescobaldi himself harvested the essence of the innovative initiative in an interview with The Vintner Project: “Here on Gorgona, surrounded by its scents and tastes, is everything one could want: love for this island, man’s loving attention, hope for a better life, the influence of the sea, and this extraordinary environment — all elements that combine to bring forth a wine that is inimitable, innately exclusive, a symbol of hope and freedom.”

RELATED: How Old Spanish Vines May Bring New Hope to the Wine Industry in the Face of Climate Change