Better sleep. Protection against anxiety and depression. Lower risks of heart disease and dementia. A longer life. According to a wealth of research in the field of behavioral medicine, these are just some of the well-being boosts associated with having a sense of purpose.

Are you in possession of this powerful elixir for living well? And if not, are you aware of how to procure it? Contrary to what many people believe, purpose isn’t necessarily ingrained in us at birth, and discovering it isn’t always like spotting a shining light from on high.

“The biggest misconception is that what that life actually looks like is going to dawn on you spontaneously, and it doesn’t,” Suzy Welch, director of the NYU Stern Initiative on Purpose and Flourishing, told Nice News. “It takes work to figure out your purpose. This is the most important work we’ll do.”

We spoke to Welch and two medical experts about what it means to have a sense of purpose, how it affects our health, and how to go about finding or rediscovering yours.

What Is a Sense of Purpose?

Alan Rozanski is a cardiologist and lifestyle medicine physician, as well as a professor at Mount Sinai’s Icahn School of Medicine. He explained that one dimension of purpose is possessing “life goals that resonate with you.” Another is having “a sense of meaning, a sense that you’re doing something that’s important.”

So, put simply: life goals that are important and meaningful — no big deal, right? Don’t worry; your calling doesn’t have to involve curing cancer to meet the criteria (though we offer a hearty thank you to any cancer researchers reading this).

Barbara Sparacino, an adult and geriatric psychologist, pointed out that there are many avenues for fulfilling one’s purpose, and they’re all dependent on our values and circumstances. She noted that someone who’s bedridden and can’t move may find it their calling to pray for others, while someone else may find meaning in sharing their perspective on social media. Both examples take energy and devotion, and both also represent how personal a sense of purpose is.

To Welch, who developed a methodology called Becoming You, purpose is defined as “the very beautiful territory” at which three aspects intersect: values, aptitudes, and interests. It’s where what we feel matters overlaps with what we’re good at and what we want to know more about.

“A Profound Health Arena”

Research around purpose began to blossom about 15 years ago, when “epidemiologically hardcore” studies on the subject first started popping up, Rozanski said, referring to the field as “a profound health arena.”

A 2016 meta-analysis he participated in found that people who had a strong sense of life purpose lived longer and developed less heart disease, while the opposite was true for those who had a low sense of life purpose. He also pointed out the wealth of data suggesting that purpose protects against cognitive dysfunction and dementia, as well as depression and anxiety. It’s similarly been linked to better sleep, higher optimism, and less loneliness.

The reasons that purpose is so potent are likely both physiological — it’s associated with less inflammation — and behavioral. “When people have a sense of being engaged in life, they tend to have better health habits as well. They’re more likely to exercise, they’re more likely to eat better, and so forth,” Rozanski said.

Welch reiterated some of those findings, but added: “We almost don’t need studies on this. I mean, empirically, people who are filled with a sense of purpose, you almost know it without them even telling you. They emanate this kind of exquisite aliveness that you want.”

How to Find Your Sense of Purpose

Identify Your Values

The first step in Welch’s Becoming You methodology is identifying your values, and she offers a science-based test on her website for doing so. This is important, she said, because the world often tells us what it thinks should matter most, leading us to make decisions that may not correspond to what we genuinely care about.

Rozanski offered another useful exercise for identifying your values, courtesy of Stephen Covey’s 1989 book, The 7 Habits of Highly Successful People. It goes like this: Imagine your own funeral. You hear four people discussing you — a family member, a close friend, a colleague, and someone from a club or activity you were involved in. What would you like them to be saying? The visualization can help you narrow in on what’s truly important to you in life.

Sparacino agreed that identifying your values is a good place to start, noting that determining how those values manifest in our lives is part of the process.

“Let’s say someone’s primary value is family: How does that show up at work? Does it mean that you leave your work at work? Does it mean that you incorporate some of your work friends as family?” she explained, adding: “The more we get to know that about ourselves, and if the way we’re behaving is aligned with our values, the better we’re able to see what works for us and doesn’t work for us.”

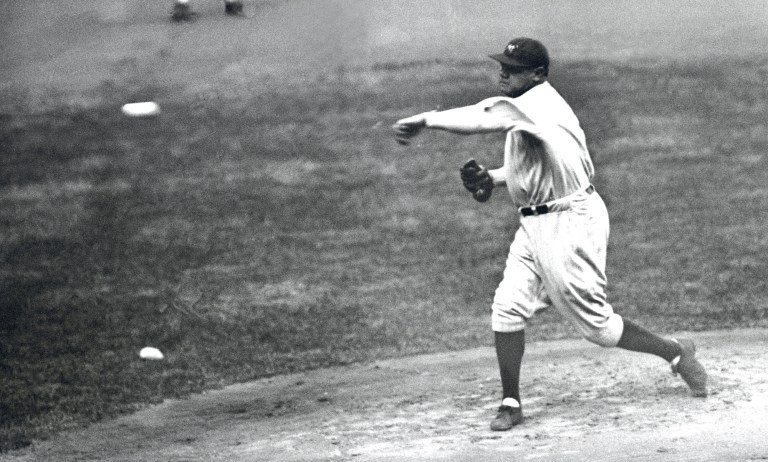

Look for “Tuning Fork Moments”

We’ve all experienced instances when time stops in the best way — when we feel energized, like we’re resonating on the same wavelength as our external actions or situation. Rozanski calls these “tuning fork moments,” and he advises paying attention to exactly what you’re doing the next time you feel one.

“I’m not talking here about generalized experiences, like going to the Grand Canyon. We’re all moved by that. I’m talking about personal experiences where you were doing something and you felt [it] resonated with you,” he said, giving writing, painting, and public speaking as examples and adding: “That’s probably a good indication of something that would be a goal in terms of a life purpose.”

Get on the Playing Field

Let’s say you’ve identified that you value personal expression, and you’ve also discovered that you feel energized when you’re making people laugh. You might consider working on a comedic one-person show with a theme that’s meaningful to you. Once you’ve got an idea like that, Rozanski suggests incorporating the pursuit into your life in a regular way, however small.

“Just maybe 15 minutes on a Sunday, but have it in your weekly schedule that those things that you really want to do you put into your life, even in a minimal step,” he said. “Once you’ve done that, you’re on the playing field. When you put it off, you’re off the playing field, [and] nothing can happen. Once you’re on the playing field, then things can happen.”

Turn to Other Mapmakers

“One of the things I think that people don’t do enough out here is to find the wise person,” said Rozanski. He explained that we all have a map in life of what’s important, but sometimes we follow a trail for years without realizing that we aren’t on the path we really wanted to take.

“As we get older, we look back and we say, ‘Gee, what was I thinking? I wish 10 years ago I had known what I know now.’ We all have that kind of feeling, but we should capitalize on that and say, ‘Wait a second, maybe I can find that better mapmaker now when I’m 30 or I’m 40, or even if I’m 60.’ There’s people who have deeper eyes than we do.”

He suggests that you share your own map (the things that matter to you, your goals, etc.) with these wise people in your life — and then be willing to implement their advice.

Volunteer

If you’re at a loss for what your purpose should be, consider looking outside yourself. Volunteering our time or resources not only benefits others, but it can also help provide a sense of usefulness, which may have the added boon of increasing our lifespan.

Rozanski pointed out a study that examined people between ages 70 and 79 who were asked how useful they felt to friends and family. Those who reported not feeling useful had a greater increase in risk for mortality over a seven-year period than those who had a strong sense of feeling useful.

Additionally, volunteering may help you discover interests and values you weren’t in tune with before. Maybe you don’t realize how much you appreciate nature until you start helping out at a botanical garden. Or perhaps your long-dormant passion for cooking becomes reignited after working shifts at a soup kitchen. Volunteering can also be short-term, like speaking at a college’s career day or picking up litter with friends. When in doubt, turn your eyes outward.

RELATED: Mediocrity Is Meaningful: The Case for Living an Average Life