Being a good Samaritan may pay off even more than you thought. While donating blood is a selfless act that can save lives and help address an urgent public health need in the U.S., there might be a good selfish reason to do it, too.

A new study from researchers at the Francis Crick Institute in London determined that giving blood often may result in genetic changes in our blood stem cells that help prevent cancers like leukemia from developing. When comparing frequent donors (individuals who gave blood three times annually over 40 years) to sporadic ones (those who gave blood fewer than 10 times total), the scientists found that the former were more likely to have favorable genetic mutations in their stem cells.

“Our work is a fascinating example of how our genes interact with the environment and as we age,” senior author Dominique Bonnet said in a news release. “Activities that put low levels of stress on blood cell production allow our blood stem cells to renew and we think this favors mutations that further promote stem cell growth rather than disease.”

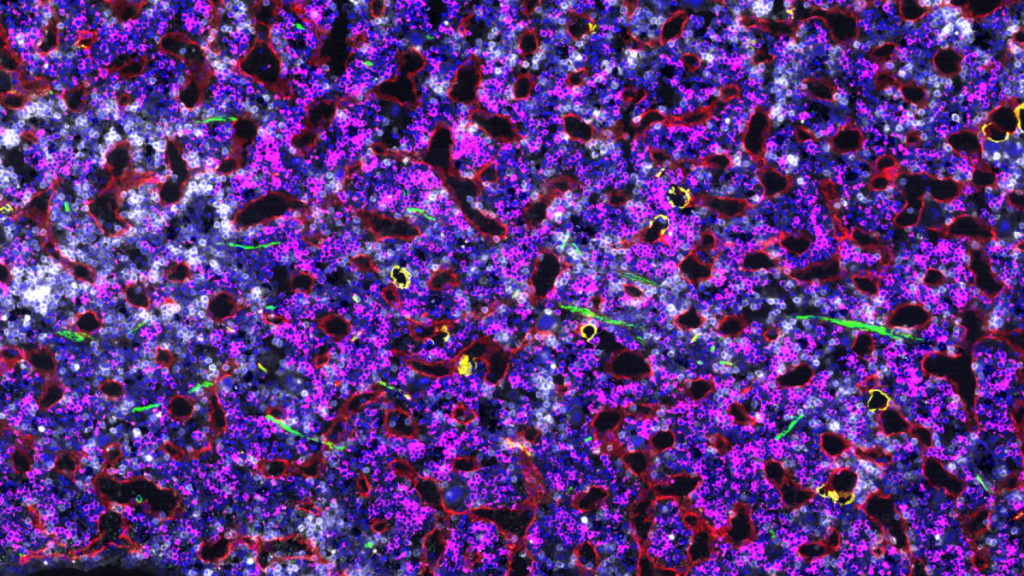

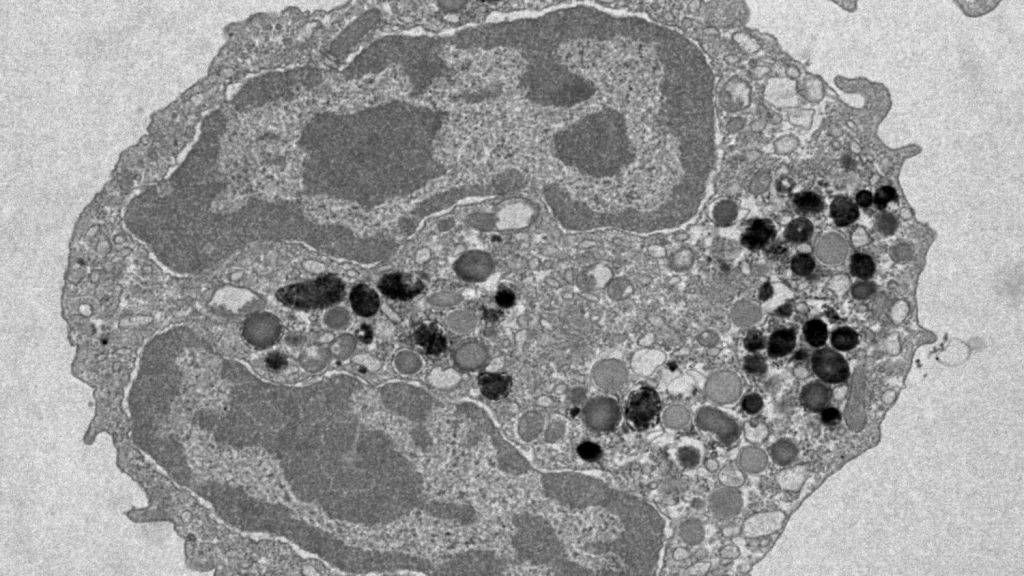

Analyzing blood from over 200 men in each category, the scientists zoomed in on hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), aka blood stem cells. These cells naturally mutate as we age, which leads to clones with subtly different genetic makeup, a process known as clonal hematopoiesis. While this is normal, certain mutations can cause blood cancers.

Giving blood didn’t affect the cells’ likelihood of undergoing clonal hematopoiesis — it was found to be just as common in frequent donors versus sporadic. However, the researchers noticed that the genetic makeup of blood cells in each group varied when it came to a gene called DNMT3A, which is known to mutate in people who develop leukemia.

This finding spurred the team — who collaborated with scientists in Heidelberg, Germany, with the help of the German Red Cross Blood Donation Center — to conduct follow-up experiments. They decided to edit human HSCs using CRISPR, and then implant the edited cells in mice. The result? When the mice that had blood removed were then exposed to stress imitating that of frequent blood loss, the cells with DNMT3A mutations produced red blood cells to recoup blood supply, and those new cells didn’t turn cancerous.

“Our sample size is quite modest, so we can’t say that blood donation definitely decreases the incidence of pre-leukemic mutations and we will need to look at these results in much larger numbers of people,” Bonnet said. “It might be that people who donate blood are more likely to be healthy if they’re eligible, and this is also reflected in their blood cell clones. But the insight it has given us into different populations of mutations and their effects is fascinating.”

While the researchers can’t yet say for sure that donating blood often makes you less likely to develop leukemia, they theorize that doing so can reduce your chances of developing early blood cancer mutations.

“We had to look at a very specific group of people to spot subtle genetic differences which might actually be beneficial in the long-term,” said Hector Huerga Encabo, postdoctoral fellow in the Haematopoietic Stem Cell Laboratory at the Crick. “We’re now aiming to work out how these different types of mutations play a role in developing leukemia or not, and whether they can be targeted therapeutically.”

RELATED: “Hungry” Fat Cells Could Fight Cancer by Devouring Tumors’ Food Sources, Study Suggests