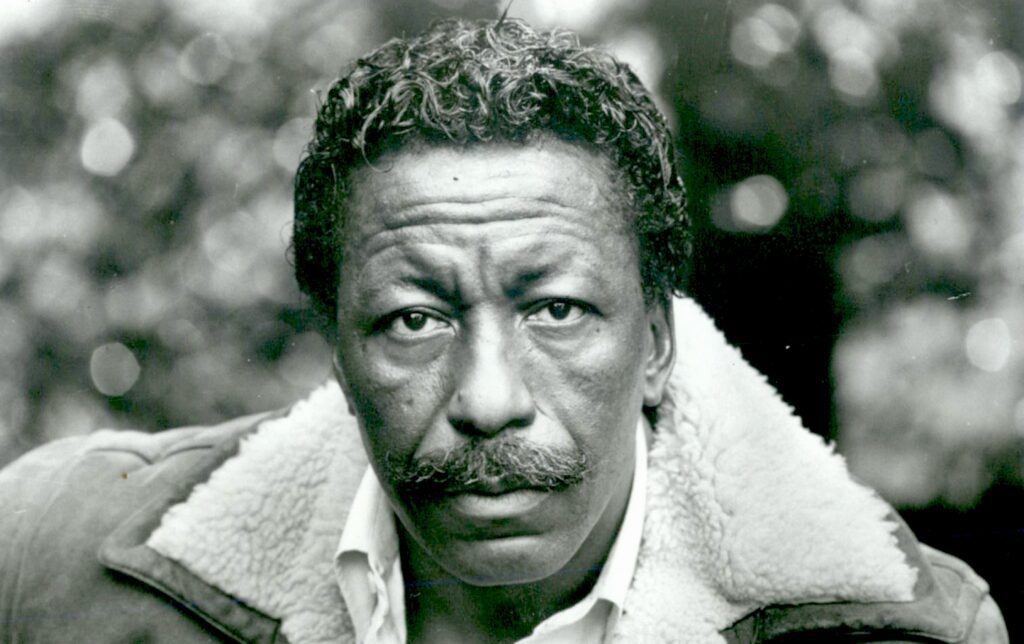

In 1948, six years before the civil rights movement would officially begin, Gordon Parks became Life magazine’s first Black staff photographer. During his nearly three decades with the publication, he made an indelible impression not only on its glossy pages, but also on American society as a whole.

Parks produced powerful photo essays that drew the public’s attention to issues like segregation and racism, but the artist was neither expected nor felt compelled to only chronicle topics connected to the color of his skin. He would often say that there was “no special Black man’s corner” for him there, according to Life. Indeed, he was also a fashion photographer and felt as comfortable snapping shots of celebrities as he did scenes related to social justice.

In addition to shooting still images, he was a filmmaker — directing the iconic 1971 film Shaft — as well as an author, musician, painter, and composer. And each of his artistic pursuits served as conduits for his humanitarianism and activism.

Parks was born into poverty in Fort Scott, Kansas, in 1912, the youngest of 15 children. He gravitated toward photography early on, intrigued by images of migrant workers he saw in a magazine while he was working as a waiter in a railway car.

View this post on Instagram

“I saw that the camera could be a weapon against poverty, against racism, against all sorts of social wrongs,” he told an interviewer in 1999, per The New York Times. “I knew at that point I had to have a camera.”

He purchased his first one at a pawn shop in 1938, and with no professional training, honed his skill to such an extent that, at age 29, he won the Julius Rosenwald Fellowship. He was awarded $1,800 — the equivalent of around $35,000 today — to support his burgeoning career. The grant helped him make his way to Washington, D.C., where he began working in the photography section of the Farm Security Administration and then the Office of War Information.

View this post on Instagram

With these agencies, he was able to “break the color line in professional photography” while creating striking images that shed light on “the social and economic impact of poverty, racism, and other forms of discrimination,” according to the Gordon Parks Foundation.

One of his most iconic photos, taken in 1942 and titled “American Gothic,” features Ella Watson, a cleaning woman who worked for the government. Echoing the famous 1930 painting by Grant Wood, she stoically holds a broom and a mop.

“I had experienced a kind of bigotry and discrimination here that I never expected to experience. … At first, I asked [Ella Watson] about her life, what it was like, and [it was] so disastrous that I felt that I must photograph this woman in a way that would make me feel or make the public feel about what Washington, D.C., was in 1942,” Parks said of the shot, per the Minneapolis Institute of Art. “So I put her before the American flag with a broom in one hand and a mop in another. And I said, ‘American Gothic’ — that’s how I felt at the moment.” The image is currently on display at the Harrison Photography Gallery in Minneapolis through June 2024.

View this post on Instagram

In 1944, Parks left his position with the Office of War Information to work on the Standard Oil Company’s long-running documentary photo project. Around the same time, he was making a name for himself by freelancing for various publications, namely Glamour, Ebony, and Vogue. Before the end of the decade, he would pitch his first photo essay to Life magazine.

The story focused on the gangs running rampant in Harlem in New York City. To ensure he had the inside scoop, he befriended a member of one of the gangs. Accompanied by the young man, just 17 years old, Parks snapped stunning, expressive pictures of both the brutality and humanity he witnessed. The resulting images, a collection published in 1948 called “Harlem Gang Leader,” impressed editors so much that they offered him a position as staff photographer.

View this post on Instagram

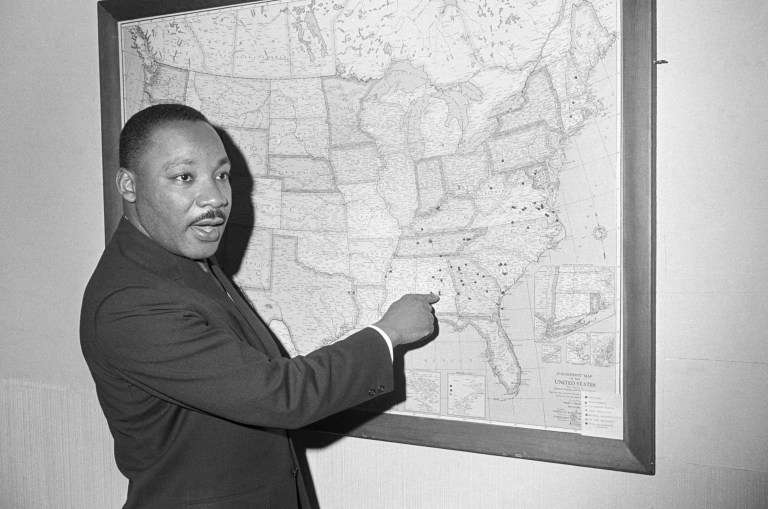

Parks continued to shoot for Life until 1972, per the Times, the same year the magazine discontinued as a weekly publication. But he didn’t stop creating. He published memoirs, novels, and poetry, directed films, and wrote the music for a 1989 ballet titled Martin, about the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.

In 1988, he was awarded the National Medal of Arts by President Ronald Reagan. And though he’d never finished high school, he received more than 50 honorary doctorates from colleges and universities. He continued evolving his various artforms until his death at age 93 in 2006, and his work continues to be exhibited decades later.

RELATED: Interactive National Mall Exhibition Features Stories Previously Untold in the Iconic Space

Pingback: 23 Forgotten Heroes History Books Deliberately Ignored - Back in Time Today